QUICK SUMMARY

The triumphal procession was the highest honor a Roman general could receive, celebrating military victory with a grand parade through the city. It blended politics, religion, spectacle, and propaganda, turning the commander into a near-divine figure for a single day.

Origins of the Roman Triumph

The triumphal procession was one of the most ancient and revered institutions of Rome. Its origins traced back to early kings and military leaders who celebrated victory through formal rituals. Over centuries, the ceremony evolved into a strictly regulated honor granted only by the Senate, reserved for generals who achieved decisive victories on foreign soil.

The triumph drew from Rome’s religious foundations. Victory was seen not merely as a military achievement but as a gift from the gods. The triumph, therefore, served as both thanksgiving and acknowledgment of divine favor. It was a sacred event, marked by sacrifices, offerings, and rituals honoring Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the supreme god who protected the Roman state.

By the Republican era, the triumph had become a symbol of Rome’s expansionist spirit. Each procession marked the incorporation of new lands, the defeat of foreign powers, and the steady rise of Roman influence across the Mediterranean world.

Requirements for a Triumph

Not every victory earned a triumph. Roman generals had to meet strict criteria before the Senate would grant the honor. The victory had to be decisive, with a significant number of enemy casualties. The war had to be formally declared by Rome, and the conflict needed to conclude with the enemy’s defeat or subjugation. Importantly, the general must have held the title of imperator, demonstrating that his troops acclaimed him as their victorious leader.

Even when these conditions were met, triumphs were not guaranteed. Politics often shaped the decision. Some generals received triumphs despite questionable achievements, while others were denied even after major victories due to political rivalries. As Rome grew, the triumph became both a military reward and a political weapon.

The Route Through the City

The triumphal procession followed a set path through Rome, transforming the city into a vast stage of celebration. The parade began outside the city walls, where the victorious army assembled with their spoils and prisoners. At dawn, the general performed purification rites and donned ceremonial clothing.

The procession entered through the Porta Triumphalis, a symbolic gateway used only for these occasions. From there, it wound through the streets of Rome, passing by crowds of citizens who gathered to witness the spectacle. It moved through the Forum Romanum, the political heart of the city, where senators, magistrates, and officials awaited. The parade concluded at the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, where sacrifices marked the triumph’s spiritual climax.

This route showcased the triumph not just as a celebration but as a reminder of Rome’s power and unity. Every step reinforced the image of the general as a guardian of the state and a chosen instrument of the gods.

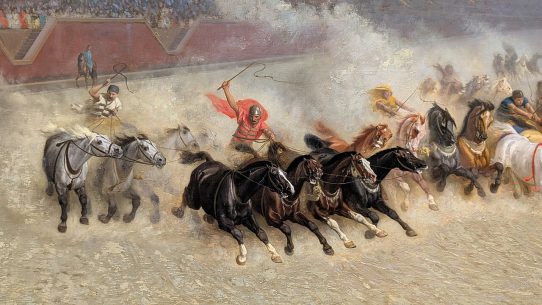

The Spectacle of the Parade

The triumphal procession was a carefully orchestrated display of wealth, dominance, and storytelling. It began with musicians, trumpeters, and heralds who announced the general’s victory to the city. Behind them marched servants carrying paintings and models depicting the conquered lands, battles, and strategic victories. These visual narratives helped Roman citizens understand the conflict, transforming distant wars into vivid scenes of conquest.

Next came the spoils of war: gold, silver, statues, rare animals, exotic treasures, and sacred relics taken from temples and palaces of defeated kings. These displays demonstrated the wealth Rome gained through expansion and reinforced the idea that victory brought prosperity to the entire community.

Captives followed, often including defeated leaders, generals, or rulers. Although their presence symbolized Rome’s supremacy, it also showed the gravity of resistance against the empire. Some captives were executed after the triumph, while others were imprisoned or enslaved.

Roman soldiers played a critical role in the procession. Not allowed to bring weapons, they marched in festive clothing, singing humorous songs that teased their general and recounted the hardships of the campaign. Their presence underscored the loyalty and discipline that made Rome’s legions unparalleled in the ancient world.

The Triumphator: A Day as a God

At the heart of the event stood the triumphator, the victorious general. On this day, he wore garments symbolic of Jupiter himself: a purple and gold toga, a laurel crown, and a tunic embroidered with stars. His face was sometimes painted red, echoing the color of Jupiter’s sacred statue on the Capitoline.

The general rode in a four-horse chariot, embodying power and divine favor. A slave stood behind him, holding a golden wreath above his head and whispering a reminder: “Remember, you are mortal.” This phrase grounded the general amid the overwhelming praise and prevented the triumph from turning into outright deification.

Even so, the triumph elevated him to near-godlike status. Citizens shouted his name, praised his victories, and treated him as a bringer of prosperity and security. For one day, he represented Rome’s highest ideal: the victorious defender of the state.

Sacrifices and Dedication on the Capitoline Hill

The triumph concluded at the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill. Here, the general offered sacrifices from the spoils of war, dedicating his victory to the god who granted success. The ritual involved the sacrifice of a white ox, symbolizing purity and divine acceptance.

Inside the temple, the general placed his laurel wreath on Jupiter’s lap, a symbolic gesture acknowledging that ultimate victory belonged to the gods. This act returned him to the human realm, ending his temporary state of divine resemblance.

The triumph closed with a great banquet, often held for senators, soldiers, and citizens. These feasts reinforced unity and reminded all participants that Rome’s strength came from shared purpose and divine blessing.

Triumphs in the Imperial Era

Under the Roman Empire, triumphs continued but became rarer. Emperors reserved them almost exclusively for themselves, viewing the triumph as imperial propaganda that reinforced their supreme authority. Generals who won victories did not receive full triumphs but instead were awarded lesser honors known as triumphal ornaments.

Emperors such as Augustus, Vespasian, and Trajan used triumphs to shape public memory. Massive sculptures, arches, and reliefs depicted their victories for generations to admire. The Arch of Titus and Trajan’s Column remain two of the most famous examples of triumphal art, preserving the spirit of the procession in stone.

As imperial rule tightened, the triumph became not just a military celebration but a powerful message about the emperor’s role as Rome’s eternal protector.

Cultural Legacy of the Triumph

The triumphal procession left a lasting mark on Roman identity and on world history. Its imagery influenced medieval coronations, Renaissance art, and even modern military parades. The concept of a grand, ceremonial march celebrating victory continues to echo through state rituals around the world.

For ancient Romans, the triumph symbolized the heart of their civilization: military excellence, religious tradition, civic pride, and belief in the gods’ favor. The procession turned victory into shared memory, reminding citizens that Rome’s greatness was both martial and sacred.

Even today, triumphal arches, inscriptions, and artistic recreations allow us to glimpse the awe and spectacle of a tradition that once filled Rome’s streets with sound, color, and celebration.