QUICK SUMMARY

The Roman calendar evolved from a lunar system into a complex civic and religious schedule that guided festivals, politics, agriculture, and everyday life. Its reforms shaped the modern calendar used worldwide today.

Origins of the Early Roman Calendar

The Roman calendar began as a lunar system traditionally attributed to Romulus, the legendary first king of Rome. Early Roman timekeeping divided the year into ten months, beginning with March and ending with December. Winter was not formally counted, and no fixed months existed for the coldest part of the year.

In this early system, March marked the rebirth of nature and the start of the military campaigning season. The year’s rhythm reflected the concerns of a small pastoral community: agriculture, warfare, and seasonal change. The early months carried names tied to gods or numbers, revealing how Romans understood time. Martius honored Mars, the god of war and spring. Aprilis likely carried associations with growth and opening. Later months, like Quintilis and Sextilis, simply meant fifth and sixth.

As Rome grew into a more organized community, the limitations of a ten-month year became difficult to manage. Religious rites, political assemblies, and farming cycles demanded more consistent measurement. These pressures led to Rome’s first significant calendar reform.

Numa’s Reforms and the Shift to Twelve Months

The second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, was traditionally credited with reorganizing the calendar. According to Roman tradition, Numa expanded the year to twelve months by introducing Ianuarius and Februarius. This reform created a year closer to the lunar cycle and established a more predictable structure for religious festival dates.

January, dedicated to Janus, the god of beginnings and transitions, became the symbolic doorway into the year. February, named for purification rites, closed the cycle with ceremonies intended to cleanse the community before spring returned.

Although Numa’s calendar improved the system, it remained tied to lunar phases. Priests known as pontifices held responsibility for aligning the calendar with seasonal reality. They occasionally inserted an extra month, Mercedonius, to keep the year synchronized with the agricultural cycle. Over time, this practice became political, allowing magistrates and priests to manipulate dates for personal advantage.

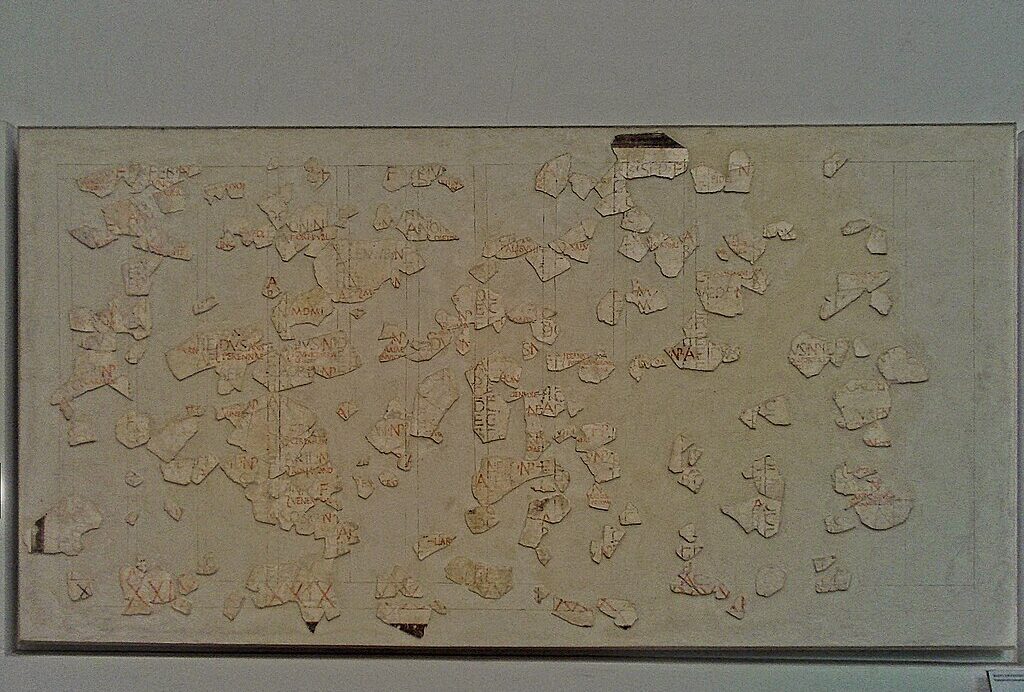

The Structure of the Roman Month

Roman months were structured differently from modern ones. Instead of numbering days consecutively, Romans counted backward from three fixed points: the Kalends, the Nones, and the Ides.

The Kalends marked the first day of the month, corresponding to the appearance of the new moon. The Nones came on either the fifth or seventh day, depending on the month, and roughly aligned with the quarter moon. The Ides occurred on the thirteenth or fifteenth and signaled the full moon. These anchor points helped orient religious rites and public duties.

Days were also categorized according to what activities were permitted. Some days allowed legal proceedings, assembly gatherings, or market activities. Others were reserved for festivals, religious observance, or solemn restrictions. Time in Rome was therefore not simply a neutral measurement but a reflection of sacred order and civic responsibility.

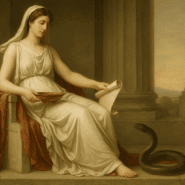

Festivals and Sacred Time

The Roman calendar was saturated with religious festivals, each woven into the agricultural and social fabric of the city. These festivals punctuated the year, marking transitions in farming seasons, honoring household deities, and celebrating the accomplishments of Rome’s mythic and historical past.

The year opened with rites to Janus, requesting his guidance for the months ahead. February included purifications, ancestor honors, and ceremonies connected to the household spirits. Spring brought celebrations dedicated to fertility, renewal, and the protection of crops. Summer festivals honored gods of growth and sunlight, while autumn ceremonies focused on harvest, thanksgiving, and preparation for winter.

Among the most important celebrations were the Lupercalia, Saturnalia, and the Vestalia. These festivals not only shaped religious life but also reinforced social bonds. Many involved public gatherings, feasting, and symbolic rituals that brought the community together.

Festivals played a central role in organizing the Roman year. They acted as cultural anchors, giving meaning to the passage of time and ensuring that religious duties remained central to civic identity.

The Republican Calendar and Its Challenges

During the Republic, the Roman calendar continued to function but suffered from increasing misalignment with the seasons. Because priests controlled the insertion of the intercalary month, political motivations often led to abuses. Leaders might lengthen the year to extend their term in office or shorten it to hasten an opponent’s time in power.

Over decades, this manipulation pushed the calendar wildly out of sync. Harvest festivals might fall in spring, and spring rites might drift toward winter. Farmers could no longer rely on the calendar to guide planting or harvesting. Religious observances began to lose their seasonal context, threatening the harmony between civic life and the natural world.

By the first century BCE, the calendar lagged so far behind reality that a major reform was necessary. This reform came under Julius Caesar, whose efforts permanently reshaped the way Rome measured time.

Julius Caesar and the Julian Calendar

In 46 BCE, Julius Caesar enacted a sweeping reorganization of the Roman calendar. Working with the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, Caesar abandoned the lunar system and introduced a solar calendar based on a 365-day year. This calendar included an extra day every four years to account for the quarter-day discrepancy in Earth’s orbit.

Caesar’s reform aligned the calendar with the seasons and laid the foundation for the modern system used today. He renamed Quintilis as Julius in his own honor, a testament to the significance of his reform. Later, Augustus adjusted minor details and renamed Sextilis as Augustus.

The Julian calendar brought stability, predictability, and scientific accuracy. It allowed festivals to return to their appropriate seasons and restored the harmony between celestial movements and civic timekeeping. Although later adjusted into the Gregorian calendar used today, the Julian reform represented one of the most influential contributions of the Roman world to global culture.

Timekeeping in Roman Daily Life

Beyond political and religious functions, the Roman calendar shaped the daily lives of ordinary people. Farmers relied on seasonal markers to guide planting and harvesting. Merchants tracked market days. Magistrates used the calendar to schedule elections, assemblies, and judicial proceedings. Families planned weddings, funerals, and private rites according to auspicious dates.

Romans also tracked the passage of years using named magistrates. Each year was marked by the names of the two consuls who held office, a system known as consular dating. Major events were recorded by referencing these officials, making historical chronology deeply intertwined with political leadership.

The calendar also interacted with broader Roman culture. Astronomy, philosophy, and civic planning all engaged with time. Roman writers, such as Ovid in his Fasti, explored the meaning behind months, festivals, and deities, giving the calendar literary and symbolic depth.

The Roman Legacy of Time

The Roman calendar evolved across centuries, shaped by kings, priests, astronomers, and emperors. From its lunar origins to its solar reform, it reflected Rome’s changing needs and expanding worldview. The calendar served as both a practical tool and a cultural map, organizing not only dates but meaning, tradition, and identity.

Its influence remains visible in the modern calendar. The names of months, the division of the year, and the concept of leap years all echo Roman innovations. Through these enduring structures, the Roman understanding of time continues to guide daily life around the world.