Mars, the formidable god of war, stood at the heart of Roman religion and identity. He was the divine embodiment of courage, discipline, and the relentless spirit that forged Rome’s destiny.

To the Romans, Mars was not merely a destroyer but a protector — the guardian of the state, the champion of order, and the father of the Roman people. His power extended beyond the battlefield to the very foundation of civilization, where strength served peace and conquest preserved justice.

Fierce in combat yet noble in purpose, Mars represented the Roman ideal of virtus: valor united with honor, victory tempered by restraint.

Name and Origin

The name “Mars” derives from the older Latin Mavors and the Proto-Indo-European root *magh*, meaning “to have power” or “to be strong.”

Unlike the Greek Ares, who embodied chaotic bloodlust, Mars was revered as a disciplined warrior and divine strategist. He was among the oldest gods of the Italic peoples, originally associated with fertility, agriculture, and the renewal of life.

As Rome grew from an agrarian society into an empire, Mars evolved from field guardian to warlord of nations, symbolizing both growth and conquest. He was the protector of Rome’s armies, the father of its founders, and the living spirit of its endurance.

Attributes and Symbols

Mars was portrayed as a youthful, powerful warrior clad in shining armor, often carrying a spear or sword and wearing a crested helmet.

His sacred animals were the wolf and the woodpecker — both symbols of courage and endurance. The wolf represented his connection to Rome’s founding myth, while the woodpecker, sacred for its vigilance, was an omen of divine favor.

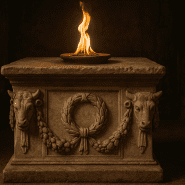

The spear of Mars was kept in his temple on the Palatine Hill and was believed to vibrate before times of war, signaling divine command. His color was red, the hue of vitality and battle, and his month — March — marked the beginning of the Roman military season.

Every symbol of Mars carried dual meaning: power guided by purpose, violence restrained by virtue.

Family and Relationships

Mars was the son of Jupiter and Juno, born of divine union or, in some versions, conceived by Juno alone through a sacred flower. He was the lover of Venus, goddess of love, and their union produced several divine children, including Harmonia and Cupid. This pairing of war and love represented the balance of passion and peace — the eternal rhythm of destruction and renewal.

Mars’s most celebrated mortal offspring were the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, born of his union with the vestal priestess Rhea Silvia. Through Romulus, the founder of Rome, Mars became the divine father of the Roman people, linking his lineage directly to the empire’s destiny.

His role as both progenitor and protector elevated him from warrior god to patriarch of Rome’s eternal power.

Myths and Stories

The myths of Mars reveal both his ferocity and his nobility. His love affair with Venus, though forbidden, became one of the most famous in myth. When her husband Vulcan discovered their secret, he trapped the lovers in a golden net and displayed them before the gods, who laughed at their folly. Yet even in embarrassment, Mars’s dignity endured — his love for Venus symbolized harmony between opposing forces: strength and beauty, war and peace.

As father of Rome’s founders, Mars’s intervention shaped history itself. When the vestal Rhea Silvia was forced into celibacy, he visited her in a dream and conceived with her the twins Romulus and Remus. After their miraculous survival and rise to power, they founded the city of Rome under his divine protection. In this myth, Mars was not a god of destruction but of creation — the source of Rome’s might and purpose.

Legends also told of his sacred shield, the ancile, which fell from heaven as a sign of his favor. To preserve it, King Numa ordered eleven identical copies made, ensuring that no enemy could steal Rome’s divine protection.

In battle, Mars was both terrifying and just. He fought alongside Rome’s heroes, guiding their arms and granting victory to the righteous. Yet his favor was never given lightly. Those who waged war without honor or discipline faced his wrath.

His duality — destroyer and defender — reflected the Roman understanding of war as a necessary tool of order rather than chaos.

Domains and Powers

Mars ruled over war, courage, military discipline, and the defense of the state. As Mars Gradivus (“the Marching Mars”), he led Rome’s legions into battle, his name invoked in the war cry of soldiers.

As Mars Quirinus, he represented peace restored through strength, presiding over citizens and civic life. His powers extended to agriculture and fertility, remnants of his earliest worship, linking the fertility of the soil with the vitality of the people.

In every domain, Mars embodied controlled energy — the will to fight, build, and persevere. His worship taught that war was not glory for its own sake but service to justice, and that peace must be earned through vigilance and valor.

Philosophy and Moral Influence

To Roman philosophers and statesmen, Mars represented the moral code of the warrior — bravery, loyalty, and obedience to duty. He embodied the virtue of virtus, the disciplined strength that upheld the state and its values.

Stoics regarded him as a symbol of active virtue, the courage to face hardship with composure. Poets like Virgil and Ovid portrayed him as both fierce and fatherly, the divine force that sustains Rome’s empire through strength tempered by justice.

Mars’s philosophy was one of balance: might in service of morality, war as a path to lasting peace. In him, the Romans saw the reflection of their highest ideal — power guided by purpose.

Temples and Worship

Mars’s worship was central to Roman religion and national identity. His most important temple, the Temple of Mars Ultor (“Mars the Avenger”), was built by Augustus in the Forum of Augustus to commemorate the defeat of Caesar’s assassins. It became a symbol of divine retribution and renewal.

Another ancient shrine, the Temple of Mars Gradivus, stood outside the city walls, where generals gathered before battle to seek his blessing. His priests, the Salii, performed sacred dances in armor each March, carrying the twelve shields of Mars through the city to mark the beginning of the campaign season.

His festivals — especially the Equirria, featuring chariot races in his honor — celebrated both his martial and agricultural aspects.

Through these rituals, Rome renewed its covenant with the god who watched over its destiny.

Legacy and Cultural Influence

As Rome’s empire expanded, Mars became the personification of Roman power itself. His name was invoked by emperors, his image emblazoned on armor and coinage, his month — March — marking the renewal of both nature and war.

In art, he remained a timeless symbol of disciplined strength, depicted as the ideal warrior, calm yet unstoppable.

His influence extended into language and astronomy: the planet Mars, red as blood and fire, bears his name as the eternal sign of vitality and struggle. In later centuries, he inspired poets, generals, and philosophers who saw in him the union of force and virtue.

To this day, Mars stands as the enduring emblem of courage and command — the god who reminds humanity that true victory lies in mastery of self as much as of battle.

Unique Traditions and Notes

Roman soldiers dedicated spoils of war to Mars, hanging their weapons in his temples as tokens of gratitude. Before campaigns, they sacrificed bulls or rams, and at the Armilustrium festival in October, they purified their weapons to end the fighting season.

The sacred spear in his temple was shaken before declarations of war, invoking his will. Wolves and woodpeckers were never harmed, for they were his sacred creatures. Even in peacetime, citizens prayed to Mars for protection, health, and strength — his presence woven into every act of courage and endurance.

Through his worship, the Romans affirmed their destiny: to conquer not only the world but their own weakness, under the vigilant gaze of Mars, eternal guardian of Rome.

Adapted from public-domain materials, including Project Gutenberg and Wikisource.