Among all the figures in Roman mythology, none stands taller than Hercules — the mighty hero whose strength defied mortal limits and whose deeds bridged the realms of men and gods.

Known to the Greeks as Heracles, Hercules became one of Rome’s most beloved cultural icons: a symbol of perseverance, courage, and triumph over suffering. His story is one of toil, redemption, and divine ascent — a mortal who earned immortality through unyielding endurance.

Origins and Birth

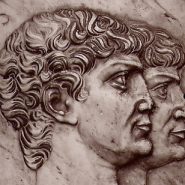

Hercules was the son of Jupiter (Zeus in Greek myth) and Alcmene, a mortal woman renowned for her virtue. His divine parentage made him a demigod, but it also drew the wrath of Juno (Hera), Jupiter’s jealous wife.

From birth, Juno sought to destroy him. According to legend, she sent two serpents to kill the infant as he lay in his cradle, but the child strangled them effortlessly — his first display of divine strength.

This act marked Hercules as extraordinary, yet his life would be one of struggle. Though blessed by his father’s power, he was doomed to face the envy and trials imposed by the queen of heaven. His tale, therefore, became one of suffering redeemed by heroism — an eternal pattern in Roman moral imagination.

The Madness and the Twelve Labors

As an adult, Hercules’ strength and bravery were unrivaled. Yet Juno’s vengeance persisted. She struck him with madness, driving him to commit an unthinkable act: in his frenzy, he killed his own wife and children.

When his sanity returned, the hero was overcome with grief and sought purification. The Oracle of Delphi commanded him to serve King Eurystheus and complete twelve impossible labors as penance.

Each labor tested his endurance, intellect, and resolve:

- The Nemean Lion: He strangled the monstrous lion whose hide no weapon could pierce and wore its pelt as armor.

- The Lernaean Hydra: A serpent with many heads, which regrew when cut — he burned each stump to prevent renewal.

- The Ceryneian Hind: A sacred deer of Diana, captured unharmed after a year-long chase.

- The Erymanthian Boar: A colossal beast subdued and carried back alive.

- The Augean Stables: He cleansed the stables of King Augeas by diverting two rivers through them.

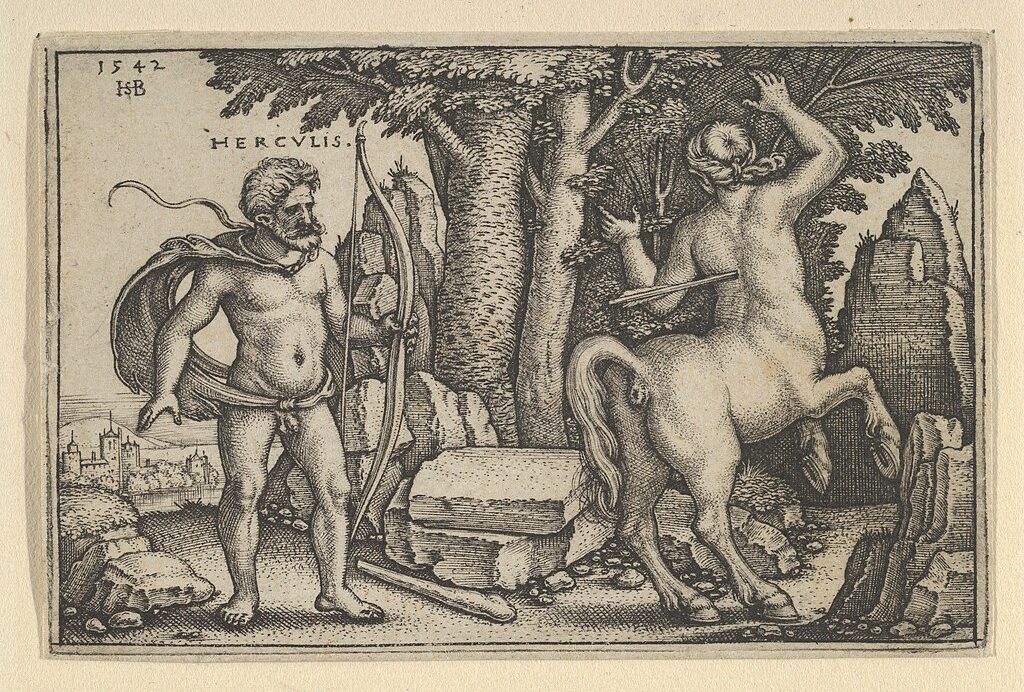

- The Stymphalian Birds: Deadly creatures with metallic feathers, driven away by his bow and a rattle given by Minerva.

- The Cretan Bull: Captured alive and released near Mycenae.

- The Mares of Diomedes: Man-eating horses tamed through cunning and strength.

- The Girdle of Hippolyta: Taken from the Amazon queen in a battle that tested both charm and might.

- The Cattle of Geryon: Won after slaying the three-bodied giant who guarded them.

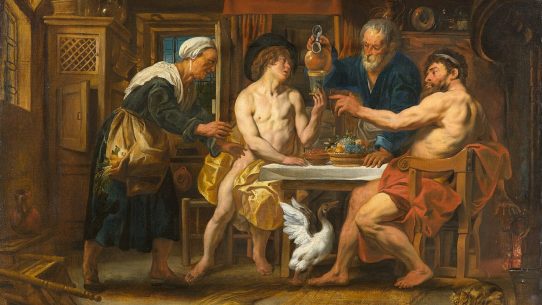

- The Apples of the Hesperides: Gained through wit, persuading Atlas to retrieve them from the garden of the gods.

- The Capture of Cerberus: Descending into the Underworld itself, Hercules brought forth Hades’ three-headed guardian, conquering death without dying.

These labors defined Hercules’ legend. They were more than feats of physical strength — they symbolized the purification of the soul through endurance and the transformation of suffering into glory.

Later Adventures and the Tragic End

Even after his labors, Hercules’ life was marked by great deeds and deep sorrow. He joined the Argonauts, fought giants and monsters, and brought justice to many corners of the world. Yet his mortal life was destined to end in tragedy.

His wife Deianira, deceived into thinking he loved another, gave him a tunic soaked in the poisoned blood of the centaur Nessus. When Hercules put it on, the venom seared his flesh, burning him with unendurable pain. Realizing his fate, the hero ascended Mount Oeta, built his own funeral pyre, and lay upon it willingly. As the flames consumed his mortal body, Jupiter descended from Olympus and granted him immortality.

Hercules rose to the heavens as a god, reconciled even with Juno, who accepted him into Olympus. There, he was united with Hebe, goddess of youth, symbolizing eternal renewal.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

In Roman culture, Hercules embodied more than brute strength — he represented the moral power of perseverance. His labors were understood as an allegory for human struggle: the conquest of chaos, passion, and weakness through courage and endurance. Temples dedicated to Hercules stood throughout Rome, including the Ara Maxima in the Forum Boarium, one of the city’s oldest sacred sites.

The Romans revered Hercules as a protector of travelers, merchants, and athletes. His story resonated with the Roman ideal of virtus — valor, discipline, and strength of character. Even emperors claimed kinship with him, presenting themselves as heirs to his divine fortitude.

In art and literature, Hercules symbolized humanity’s ascent through struggle. His apotheosis — his transformation from man to god — expressed Rome’s belief that mortal virtue could achieve immortality through action and honor.

Legacy

The legend of Hercules transcended time, surviving in medieval and Renaissance art, Renaissance humanism, and modern storytelling. He became a universal symbol of endurance, his labors retold as parables of moral and spiritual conquest.

From ancient mosaics to Baroque sculptures, from Shakespeare’s plays to Hollywood films, the image of Hercules persists — timeless, enduring, and ever heroic.

Hercules remains the eternal bridge between man and god: a reminder that greatness is not bestowed but earned through suffering, courage, and resolve.