QUICK SUMMARY

The Cult of Mithras was a mysterious Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras, known for its underground temples, secret initiation rites, and imagery of heroism and cosmic salvation. Popular among soldiers, it flourished across the empire from the first to fourth centuries CE before declining with the rise of Christianity.

Origins and Identity of Mithras

The Cult of Mithras occupied a unique place in the spiritual landscape of the Roman Empire. While many deities of Rome evolved from older Italic, Greek, or Etruscan roots, Mithras had a distinctly eastern origin. His name and certain mythic elements echoed the Indo-Iranian god Mithra, associated with contracts, light, and divine truth. The Roman version of Mithras, however, was not a simple continuation of this earlier deity. Rather, he emerged as a transformed, distinctly Roman figure shaped by imperial culture, military life, and the secretive nature of mystery religions.

In Roman art and inscriptions, Mithras was consistently portrayed as a youthful hero wearing a Phrygian cap and a flowing cloak, standing at the center of the cult’s most iconic scene. Yet despite his recognizable imagery, no surviving scripture describes his origin story or divine lineage in a systematic way. Most of what is known is reconstructed from archaeology, temple inscriptions, and comparative mythology.

The broader Persian world influenced the Roman imagination, and Mithras became a bridge between East and West. He was adopted not as an imported foreign god but as a cosmic hero whose deeds symbolized life, death, and renewal. His worshipers saw him as a powerful intermediary between humanity and the divine, a figure who maintained order in the universe.

The Spread of Mithraism Across the Roman Empire

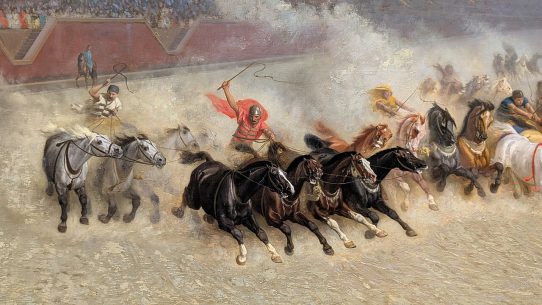

The rise of Mithraism coincided with the height of Roman imperial expansion. By the first century CE, Mithraic temples, known as mithraea, began appearing across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. The cult gained particular strength among soldiers, merchants, government officials, and others who lived far from home.

Mithraea have been found along the Rhine and Danube frontiers, in Britain, in the heart of Rome, and even as far east as Syria and the fringes of Persia itself. This geographic range shows the broad appeal of the cult’s promise: loyalty, brotherhood, and spiritual protection. For a soldier stationed at a distant border fort, Mithras offered a sense of belonging, shared ritual, and cosmic purpose.

In urban centers, the cult attracted administrators, traders, and men involved in the machinery of empire. Unlike the public ceremonies of Jupiter or Mars, Mithraic worship unfolded in private settings. Only initiates could participate, creating a close-knit spiritual community within Rome’s vast and often impersonal world.

The Mithraeum: Temples of Mystery and Darkness

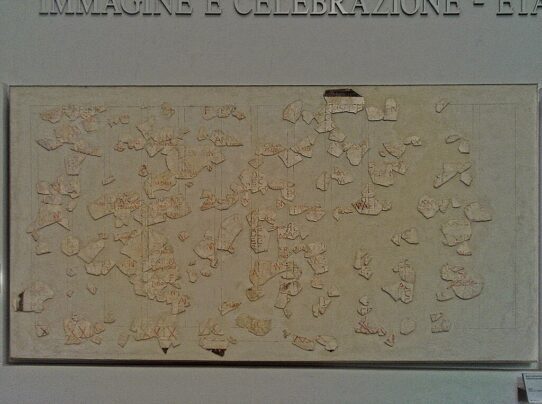

The architecture of Mithraic temples reflected the secretive nature of the religion. Mithraea were typically underground or built to imitate caves, recalling the mythic setting where Mithras performed his most famous act: the slaying of the cosmic bull.

Inside these temples, a narrow central aisle ran between raised benches where initiates reclined during communal meals. At the far end stood the cult’s central relief: Mithras, in mid-action, plunging a dagger into a sacred bull while various animals and celestial symbols surrounded him. This tableau, known as the tauroctony, appeared in every mithraeum, indicating its importance to the cult’s theology.

The atmosphere inside a mithraeum was dim, enclosed, and symbolic of the cosmic cave. Lamps and torches cast flickering shadows along the murals and carved figures. The setting was meant to transport initiates beyond ordinary life, immersing them in a symbolic world of struggle, triumph, and spiritual ascent.

Because mithraea were small, most initiated groups numbered around twenty to forty men, fostering a sense of fraternity. Meals, oaths, and rituals took place in this intimate environment, reinforcing the bonds between members.

Initiation and the Seven Grades of Membership

Mithraism was a mystery religion, meaning its most important teachings were secret and restricted to initiates. New members entered through a series of initiation rites that tested their bravery, loyalty, and commitment. Though the details remain largely unknown, archaeological evidence hints that these tests might have included trials of heat, cold, hunger, or symbolic reenactments of cosmic struggles.

The cult was structured around seven grades of initiation. Each grade represented a stage of spiritual progression and carried distinct titles, symbols, and ritual responsibilities:

- Corax (Raven)

- Nymphus (Bridegroom)

- Miles (Soldier)

- Leo (Lion)

- Perses (Persian)

- Heliodromus (Sun-Runner)

- Pater (Father)

Advancing through the ranks was both a personal spiritual journey and a social ascent within the cult. Higher grades often involved closer proximity to the sacred mysteries, including deeper knowledge of the cosmic symbolism embodied in the bull-slaying scene.

The top rank, Pater, represented wisdom, authority, and the role of spiritual fatherhood. Within each mithraeum, the Pater presided over rituals and guided initiates through the stages of transformation.

The Meaning of the Bull-Slaying Myth

At the heart of the cult stood the tauroctony, a dramatic and enigmatic image that appeared in every Mithraic temple. The scene shows Mithras overpowering a powerful bull and plunging a knife into its side as a serpent, dog, scorpion, and other creatures gather around.

Despite its prominence, no surviving ancient text explains the myth in full. Scholars generally interpret it symbolically rather than literally. The bull represented primal vitality, and its sacrificial death generated new life. In Roman interpretations, the act symbolized the cosmic cycle of death and rebirth, the turning of seasons, and the renewal of spiritual strength.

The surrounding animals reflected constellations, linking Mithras to the heavens and marking him as a guide through the cosmic order. The sun and moon often appeared above the scene, reinforcing the cult’s astronomical symbolism.

Some initiates likely understood the tauroctony as a metaphor for overcoming inner chaos, conquering ignorance, or aligning oneself with the cosmic forces of light and truth. Others may have viewed it as a historical or mythic event performed by the god in primordial time. Whatever its precise meaning, the bull-slaying stood as a powerful emblem of transformation.

Rituals, Brotherhood, and Daily Practice

Mithraic worship involved ritual meals, symbolic purification, and the reenactment of mythic events. Communal feasting on the raised benches formed the heart of many gatherings. Members likely shared bread, wine, and other offerings in imitation of the cosmic banquet between Mithras and the Sun.

The cult emphasized loyalty, courage, honor, and duty. These values resonated strongly with soldiers, explaining the religion’s popularity within the Roman legions. Members saw themselves as part of a sacred brotherhood, bound not only by shared rituals but by shared moral ideals.

Mithraism did not require abandonment of other Roman religious practices. Initiates could worship Jupiter, Mars, or household gods while also participating in Mithraic rites. The cult offered a spiritual supplement rather than a replacement, providing a private space for reflection and symbolic renewal.

Competition with Christianity and Decline

By the third and fourth centuries, Mithraism reached its peak. Temples flourished in major cities, and the cult’s imagery appeared on gems, sculptures, and inscriptions throughout the empire. Its structure, symbolism, and promise of salvation bore similarities to early Christianity, triggering occasional comparisons and tensions.

As Christianity gained imperial support in the late fourth century, mystery religions declined. Christian emperors enacted laws restricting pagan worship, and mithraea were closed, repurposed, or destroyed. The Cult of Mithras faded from view, leaving behind only its stone chambers and mysterious reliefs.

Yet its legacy endured in subtle ways. The imagery of light overcoming darkness, the importance of spiritual brotherhood, and the idea of personal transformation through symbolic rites remained part of the broader cultural memory of Rome.

Legacy and Modern Fascination

Today, the Cult of Mithras is one of the most studied mystery religions of antiquity. Its blend of eastern influence, Roman adaptation, and secret ritual continues to fascinate archaeologists and historians. The survival of mithraea beneath modern cities offers rare glimpses into the private spiritual lives of Roman men.

Mithras stands as a testament to Rome’s diverse religious landscape. In a world filled with public ceremonies and state cults, Mithraism offered something intimate, symbolic, and deeply personal. It invited initiates into a hidden world where cosmic drama unfolded quietly beneath the empire’s bustling streets.