Among the ancient guardians of Rome, few deities stand as firmly in the shadowed crossroads between myth, politics, and early religion as Quirinus.

Once a powerful figure in Rome’s earliest divine triad, Quirinus embodied the ideals that held the Roman state together: unity, citizenship, and the transformation of a people from wandering warriors into an ordered society. Though later overshadowed by Jupiter and Mars, Quirinus remains one of the most revealing windows into Rome’s earliest identity.

The Origins of Quirinus

Quirinus is among the most ancient of Roman gods. His earliest worship predates much of the structured pantheon, and he was originally tied to the Sabine people, whose customs and beliefs merged with early Rome. His name may come from quiris, meaning “spear,” suggesting martial roots, but it also connects to Quirites, the formal term for Roman citizens.

This dual meaning hints at the nature of Quirinus: a god who represented both the warrior past and the orderly civic future.

The Early Capitoline Triad

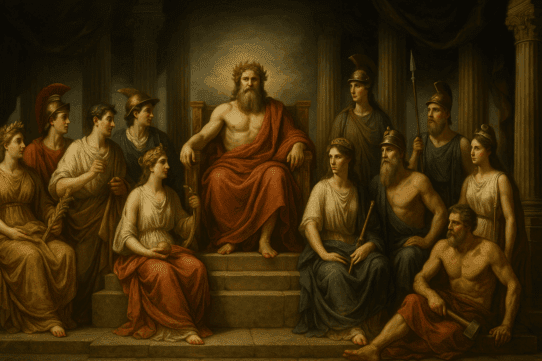

Before Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva dominated Roman religion, Rome honored an older triad:

- Jupiter – the sky and supreme authority

- Mars – the vitality of war

- Quirinus – the civic and communal life of the Roman people

In this arrangement, Quirinus completed a symbolic cycle. Mars represented Rome at war; Quirinus, Rome at peace. Together, they created a rhythm of action and restoration that defined Roman life.

As society grew more complex, Quirinus gradually faded into the background, but the foundations of his cult remained embedded in Roman religious memory.

Quirinus and Romulus: A Divine Transformation

One of the most enduring aspects of Quirinus is the belief that he was the deified form of Romulus, Rome’s legendary founder.

According to early tradition, Romulus did not die but instead vanished into a storm of divine light. When the sky cleared, he had become Quirinus, guardian of the Roman state. This apotheosis reinforced a powerful idea: Rome’s political identity was divinely sanctioned.

By tying Romulus to Quirinus, the Romans united myth with civic ideology. The city’s founder did not merely create Rome—he continued to protect it forever.

Symbols and Sacred Associations

Although Quirinus never developed the elaborate mythology seen with other gods, certain symbols became closely tied to him:

- the spear, representing both martial beginnings and ancestral authority

- the curule chair, symbolizing civic leadership

- the Quirinal Hill, one of Rome’s earliest inhabited regions and a center of his cult

These symbols reflect a god whose authority rested not merely in myth but in the lived experience of Roman citizenship.

The Flamen Quirinalis

Quirinus had a dedicated high priest — the Flamen Quirinalis — one of Rome’s three major flamines, alongside the priests of Jupiter and Mars. This elite priesthood reveals how significant the god once was.

The Flamen Quirinalis oversaw several ancient festivals, including:

- Quirinalia, a day honoring Quirinus and marking the end of Rome’s winter hardships

- rites connected to early agricultural practices

- ceremonies celebrating civic unity

Through these rites, Quirinus remained a quiet but persistent presence in Roman religious life.

Quirinus in Everyday Roman Identity

While many Roman gods ruled over realms of nature, war, or love, Quirinus governed something more subtle: the social body of Rome itself. He was the divine representation of:

- citizens working together

- the integrity of the state

- the peaceful order that followed warfare

- the shared identity that bound Romans through law, duty, and heritage

In this sense, Quirinus served not only as a deity but as an ideal — a reminder that Roman greatness depended on unity as much as military power.

Decline and Survival

As Rome expanded and its pantheon absorbed gods from Greece and beyond, Quirinus gradually became less central. Jupiter, Mars, and imported gods such as Apollo and Minerva overshadowed him.

Yet he never disappeared completely. His hill remained one of the most prestigious in Rome, his priesthood continued, and his association with Romulus ensured his story stayed woven into Rome’s origins.

Today, Quirinus stands as one of the oldest guardians of Roman identity — a figure who still illuminates the earliest chapters of Roman religion.

Conclusion

Quirinus is a reminder that Rome viewed its own society as something sacred. In him, the Romans worshipped not just a god but an ideal: citizenship, unity, and the duty of a people to uphold the state they built.

Through myth and ritual, Quirinus preserved the earliest Roman belief that a city’s strength came not only from its soldiers and kings but from the collective spirit of its citizens.