Apollo, the radiant god of the sun, music, and prophecy, stood among the most revered and complex deities of the Roman pantheon.

To the Romans, he represented light in its many forms — physical, intellectual, and spiritual. He was the bringer of truth and harmony, the divine patron of poetry, healing, and the arts. His presence embodied clarity, balance, and order: the triumph of reason over chaos.

Though adopted from Greek mythology, Apollo’s Roman identity grew into that of a universal god, illuminating every realm from medicine to morality. He was both destroyer and healer, whose golden light revealed the path of wisdom and the rhythm of divine perfection.

Name and Origin

The name “Apollo” is thought to derive from the Greek Apóllōn, possibly meaning “bright” or “pure.” Unlike many Roman gods, Apollo retained his original Greek name and attributes, reflecting Rome’s deep admiration for Greek culture and philosophy.

Introduced to Rome around the 5th century BCE, his worship gained prominence during times of plague and uncertainty, when his powers of purification and prophecy were invoked to restore balance. The Romans saw in Apollo not only the radiant archer of myth but also the symbol of enlightenment — the divine intelligence that guided civilization toward truth and harmony.

Attributes and Symbols

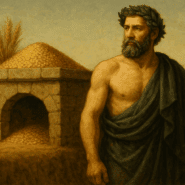

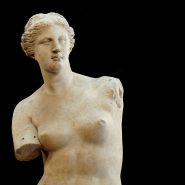

Apollo was depicted as a youthful, athletic god crowned with laurel leaves, the emblem of victory and poetic inspiration.

His most recognizable symbols included the lyre, the bow, the laurel wreath, and the sun chariot. The lyre represented music and order — the harmony of the cosmos expressed in sound — while the bow symbolized precision and divine justice.

His sacred animals were the swan, dolphin, and raven, each tied to prophecy and purity. In art, he stood as the eternal ideal of beauty and intellect, embodying the balance between mind and body that Romans admired as the essence of virtue.

Family and Relationships

Apollo was the son of Jupiter and Latona (Leto), and the twin brother of Diana, goddess of the moon and the hunt. Their birth, after Latona’s flight from Juno’s jealousy, was said to have taken place on the floating island of Delos, which became sacred to both.

Though Apollo had many loves, both mortal and divine, most of his romances ended in tragedy, serving as lessons in the fleeting nature of desire. His love for Daphne, the nymph who fled his pursuit and was transformed into a laurel tree, symbolized the transformation of passion into eternal art — for from her leaves came his sacred crown.

Other tales spoke of his union with the mortal Coronis, mother of Asclepius, god of medicine, and his affection for Hyacinthus, a youth transformed into the hyacinth flower after his untimely death.

Through these stories, Apollo’s love was shown as both creative and destructive, revealing the divine tension between emotion and order.

Myths and Stories

Apollo’s myths span the full range of human experience — from triumph to tragedy, wisdom to wrath.

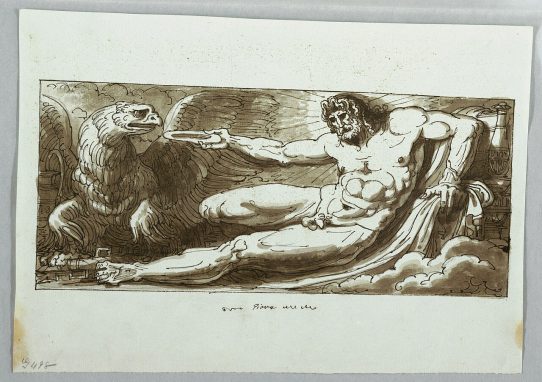

One of his earliest feats was slaying the monstrous serpent Python, which had infested the sacred site of Delphi. By killing the serpent and cleansing the land, Apollo claimed the oracle as his own, establishing the famed Oracle of Delphi, where his priestess, the Pythia, spoke his prophecies. Through her, kings and commoners alike sought guidance, believing Apollo’s wisdom to bridge the gap between divine truth and mortal uncertainty.

Another celebrated tale recounts Apollo’s punishment of Niobe, queen of Thebes, who mocked his mother Latona and boasted of her many children. In vengeance, Apollo and his sister Diana struck down Niobe’s offspring, sparing only a few. The myth reminded mortals of the dangers of pride before the divine. Yet Apollo was not solely a god of wrath.

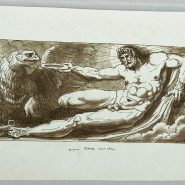

When his son Asclepius defied the natural order by resurrecting the dead, Jupiter struck the healer down with a thunderbolt. In grief, Apollo avenged him by slaying the Cyclopes who had forged the weapon — an act that led to his own exile among mortals. There, he served King Admetus as a shepherd, tending flocks and blessing the land with prosperity. This episode revealed his dual nature: a god of immense power who understood humility and labor.

In another myth, Apollo competed with the satyr Marsyas in a contest of music. When Marsyas challenged the god to play the flute better than he the lyre, Apollo accepted but demanded that they play upside down — an impossible task for the satyr. When Marsyas failed, Apollo punished him harshly, flaying him alive as a warning against hubris. Though cruel, the tale illustrated Apollo’s unwavering devotion to perfection, art, and divine order — ideals that defined the Roman sense of discipline and beauty.

Domains and Powers

Apollo’s domains encompassed light, prophecy, music, healing, and purity. He governed the sun’s daily course and the harmony of the cosmos, acting as mediator between divine will and human fate.

As the god of prophecy, his voice was truth itself — the principle of order expressed through wisdom. He was also a healer, capable of bringing and curing disease, for light could both burn and cleanse. His lyre symbolized not only art but the moral structure of the universe — each string a note in the divine composition of existence.

In his duality, Apollo ruled both the rational and the spiritual, embodying the unity of knowledge, beauty, and discipline.

Philosophy and Moral Influence

Roman philosophers regarded Apollo as the embodiment of reason and clarity. The phrase “Know thyself”, inscribed at his temple in Delphi, became a moral axiom: wisdom begins with self-awareness.

Stoics viewed him as the divine intellect that brings order to chaos, while poets invoked him as patron of inspiration and eloquence. His worship taught moderation — the balance between passion and restraint, light and shadow.

In Apollo’s radiance, Romans saw the ideal of harmony between mind and emotion, art and virtue. He was the god of civilization itself: the light that guides humanity from ignorance to understanding.

Temples and Worship

Apollo’s cult was among the most honored in Rome. His great temple on the Palatine Hill, dedicated by Augustus in 28 BCE, symbolized the emperor’s vision of order, culture, and renewal. Within its walls stood libraries, artworks, and the Sibylline Books of prophecy.

Festivals such as the Ludi Apollinares were held in his name, featuring games, music, and theatrical performances. His priests offered laurel and incense, while his devotees prayed for clarity and health.

Unlike more mysterious cults, the worship of Apollo was public and serene — a celebration of enlightenment and the triumph of reason.

Legacy and Cultural Influence

Apollo’s influence extended beyond religion into art, science, and philosophy. His image became the model of youthful perfection and intellectual grace, shaping Western ideals of beauty for centuries.

In Renaissance art, he symbolized enlightenment, and in literature, he became the muse of poets and thinkers seeking truth through art. The term “Apollonian” came to represent order, clarity, and rational beauty — the counterbalance to the “Dionysian” chaos of Bacchus.

The Apollo of Rome lives on not only in myth but in every pursuit of knowledge, art, and harmony that seeks to bring light to the human mind.

Unique Traditions and Notes

The laurel wreath, sacred to Apollo, was worn by poets, scholars, and victors as a mark of inspiration and excellence.

Musicians dedicated their instruments to him before performances, seeking divine favor. At Delphi, his oracle’s prophecies were delivered in poetic verse, emphasizing that truth itself was a form of art. In Rome, he was invoked at the start of poems, battles, and healings alike.

Through Apollo, the Romans honored the belief that illumination — of the body, mind, and spirit — is the highest form of divinity. His light continues to shine in every act of creation and understanding.

Adapted from public-domain materials, including Project Gutenberg and Wikisource.