Among the grandest celebrations of the ancient Roman calendar stood the Ludi Romani, or “Roman Games.” These were not mere spectacles of sport and theater — they were sacred rituals, expressions of Rome’s devotion to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the greatest and most powerful of the gods. Through athletic contests, dramatic performances, and solemn sacrifices, the Romans renewed their covenant with their divine protector, believing that civic order and victory flowed from Jupiter’s favor.

Origins and Early History

The Ludi Romani are among the oldest of Rome’s public festivals. Tradition holds that they began in the sixth century BCE during the reign of Tarquinius Priscus, Rome’s fifth king, though some ancient writers credited their formal institution to Aulus Postumius Albus after Rome’s victory over the Latins at Lake Regillus. Originally, the games were a spontaneous act of thanksgiving — a vow to Jupiter in exchange for divine aid during war — but over time they evolved into a fixed annual event, woven into the rhythm of Roman life.

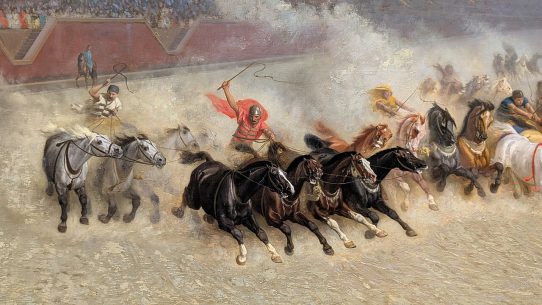

By the late Republic, the games took place every September, coinciding with Jupiter’s festival season, and were held primarily in the Circus Maximus, the enormous arena between the Palatine and Aventine hills. The sight of thousands gathered beneath the open sky, watching chariot races offered to the King of the Gods, embodied the unity of religion and state.

Sacred Structure and Ceremony

The Ludi Romani were divided between religious rites and public entertainments, a pairing that reflected Roman belief in the harmony between piety and pleasure. The ceremonies began with a grand procession known as the pompa circensis, a ritual parade that wound its way through the city to the Circus Maximus. Leading the procession were young noblemen on horseback, followed by athletes, musicians, and priests bearing sacred vessels. Images of the gods, including a magnificent statue of Jupiter himself, were carried on decorated wagons.

When the procession reached the circus, priests performed animal sacrifices — often oxen or white bulls — before the opening of the games. The smell of incense and the smoke of offerings rose toward the heavens, an invitation for Jupiter to witness and bless the festivities. Only after these rites were complete could the races begin.

Spectacle and Competition

To the Roman people, the games were as thrilling as they were holy. Chariot races dominated the Ludi Romani, featuring teams drawn from the famous stables of the four factions — Red, White, Blue, and Green. The contests were accompanied by wild cheers, wagers, and songs of triumph, but even amid the chaos, every lap was dedicated to the god above.

In later centuries, the Ludi expanded to include dramatic performances (the ludi scaenici), with plays by writers such as Plautus and Terence staged in Jupiter’s honor. These theatrical additions marked the growing sophistication of Roman religious culture — a recognition that art, like war and sport, could also be an offering to the divine.

Political and Civic Meaning

The Ludi Romani were more than entertainment; they were instruments of statecraft. Each year, the aediles — magistrates responsible for organizing the games — used them to demonstrate their generosity, competence, and devotion to the gods. Lavish spectacles could win political favor, while failure to please the crowds risked disgrace.

For the common people, the games were a visible expression of Rome’s greatness. To watch the races was to participate in the story of the city itself — a story blessed by Jupiter. As the empire grew, emperors and generals alike used the Ludi to display their triumphs, dedicating spoils of war to Jupiter’s temple on the Capitoline Hill.

Religious Significance and Legacy

At its heart, the Ludi Romani were acts of gratitude and reaffirmation. Each offering, each chariot wheel that turned beneath Jupiter’s gaze, was a reminder that Rome’s prosperity depended on divine order. The games symbolized the balance between mortal ambition and divine restraint: the people could celebrate their might, but only under the watchful eyes of the gods.

Even after the fall of pagan worship, echoes of the Ludi survived in later Roman festivals, imperial triumphs, and eventually in Christian feast days that inherited their pageantry. The spirit of public celebration — where faith, art, and spectacle intertwine — can trace its lineage back to the days when Jupiter’s thunderbolt shone over the Circus Maximus.