Rome did not merely conquer territories. It absorbed cultures, absorbed beliefs, and wove foreign gods into its expanding religious fabric. This willingness to integrate deities from abroad helped create one of the most diverse and adaptable pantheons in the ancient world.

Roman religion became a living archive of Mediterranean spirituality, shaped by diplomacy, conquest, trade, and curiosity.

Rome’s Open-Door Approach to Divinity

From its earliest days, Rome embraced the idea that the gods of other peoples possessed real power. Welcoming foreign deities was considered practical and politically stabilizing.

If a conquered people saw their gods honored in Rome, resistance softened. At the same time, Romans believed that favoring outside gods improved their own fortunes. Divine power was not exclusive, and an additional god meant an additional source of protection.

This philosophy created a religious system that was flexible, expansive, and often deeply syncretic.

Greek Influences and the Birth of Roman Classics

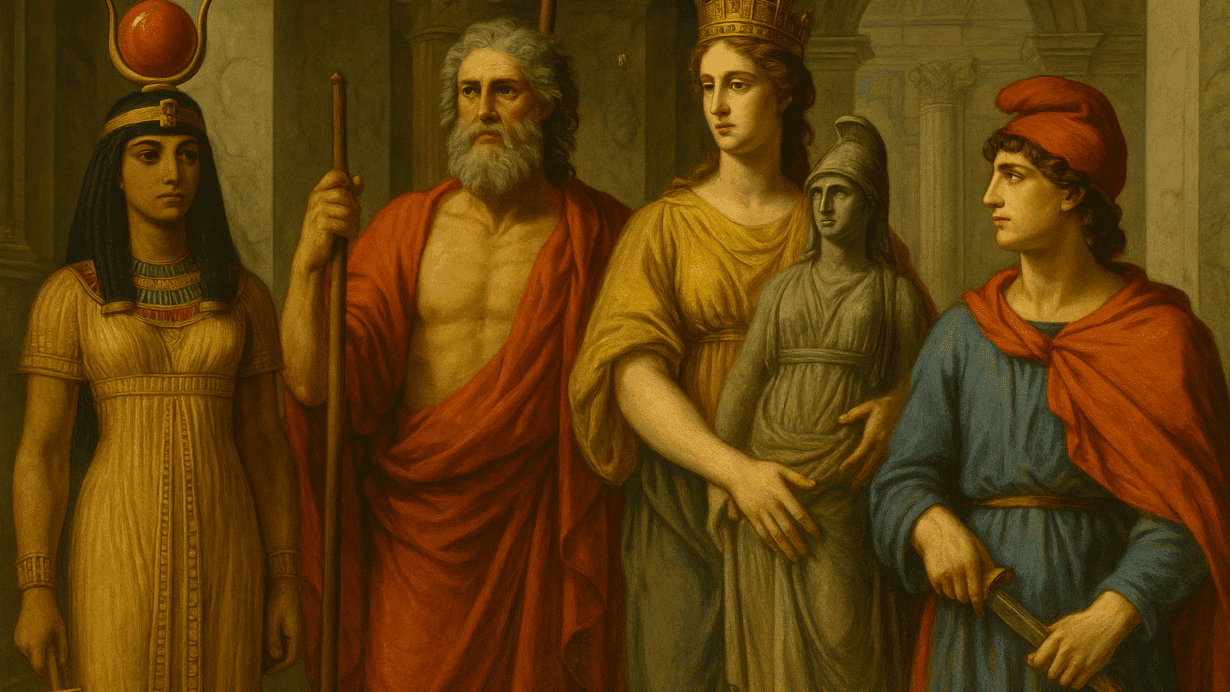

The most significant foreign influence came from Greece. Through trade with Southern Italy and later through conquest, Greek gods were gradually adopted and reshaped. Zeus became Jupiter, Hera became Juno, and Ares became Mars. Sometimes Rome imported not just the deity but also the rituals and priestly customs surrounding that god.

Greek myths were reinterpreted to align with Roman virtues. Heroes such as Heracles became Hercules, celebrated not only for strength but also for endurance and civic contribution. The blending of Greek identity with Roman values helped establish the classical image of the Roman pantheon known today.

Etruscan Divinities and Rituals

Before Greece’s influence, the Etruscans shaped Rome’s early religious framework. Their gods, divination practices, and temple designs left a deep imprint.

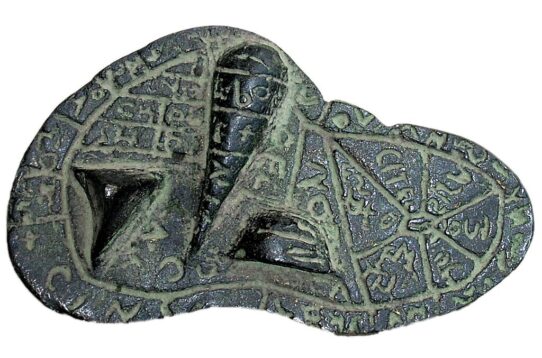

Tin, the Etruscan sky father, paralleled Jupiter. Uni influenced the Roman understanding of Juno. Even the Roman liver-reading ritual, haruspicy, came from Etruscan priests who interpreted omens through the organs of sacrificed animals.

The Etruscans also provided Rome with powerful guardian figures such as Tages, the prophetic child, and the Vanth and Charun spirits associated with the underworld. These beings contributed to Rome’s evolving vision of fate and death.

Egyptian Gods and the Allure of the East

Egypt became a wellspring of fascination in the late Republic. As Roman elites traveled to Alexandria, Egyptian religion entered Roman life with an exotic appeal.

Isis, the powerful mother goddess and patron of sailors, became deeply popular. Serapis, a Hellenistic-Egyptian healing god, was equally embraced. Temples dedicated to Isis and Serapis rose across Rome, offering mystery rites, purification rituals, and a promise of personal salvation.

These gods operated differently from the formal, state-focused Roman cults. Their emotional, individualistic nature attracted wide audiences, especially among the urban poor and freedmen.

Syrian and Near Eastern Cults

As Rome expanded through the Near East, it encountered deities with intense devotional followings.

The Syrian goddess Atargatis, called Dea Syria in Rome, symbolized fertility and the life-giving power of water. Adonis, beloved youth of Near Eastern myth, gained renewed popularity through Roman poetry and seasonal rituals. Even Baal and local storm gods found places in Roman worship, often reframed within Jupiter’s sphere of influence.

These cults offered ecstatic rites, music, and communal celebrations. Their presence showed Rome’s willingness to accept forms of worship that were emotional and foreign yet spiritually powerful.

The Persian God Mithras and His Legionnaire Following

Mithras was not worshipped publicly but in private underground sanctuaries called mithraea. His cult, likely adapted from Persian traditions, became especially popular among soldiers. The imagery of Mithras slaying the cosmic bull symbolized strength, loyalty, and triumph over chaos.

Ritual meals, graded initiations, and strict brotherhood shaped this imported mystery religion into a uniquely Roman institution. Mithraism never became a state religion, but it stood as one of Rome’s most influential foreign imports.

Celtic and Germanic Spirits of the Provinces

In the western provinces, Rome encountered the local gods of Gaul, Britain, and Germany. Many were not replaced but blended with Roman deities.

Lugus merged with Mercury. The mother-goddess Matrona aligned with Juno or Fortuna. Local war gods became companions or aspects of Mars.

This blending gave conquered peoples a sense of continuity. At the same time, Rome enriched its own pantheon with deities rooted in nature, fertility, rivers, and tribal identity.

The Political Strategy Behind Divine Adoption

Rome often imported foreign gods deliberately to ensure victory or secure loyalty. During times of crisis or war, the Senate could consult the Sibylline Books and be instructed to bring in a new deity. When Hannibal threatened Rome, the goddess Cybele (Magna Mater) was welcomed from Phrygia to stabilize the state. Similar acts occurred during droughts, plagues, or military stalemates.

This practice reflected a worldview in which divine alliances were as essential as political ones. Just as Rome built coalitions among nations, it gathered a coalition of gods.

How Foreign Gods Changed Roman Religion

The inclusion of outside deities did more than expand the pantheon. It transformed Roman spirituality in several ways.

It encouraged syncretism, blending identities and creating new interpretations of familiar gods. It introduced personal and emotional religious experiences through mystery cults. It brought artistic influences from Greece, Egypt, and Persia. Most importantly, it allowed Roman religion to evolve with the empire itself.

The resulting system was complex and multi-layered, where local traditions, imported beliefs, and state rituals coexisted.

A Pantheon as Vast as the Empire

By its height, the Roman Empire contained hundreds of cults, rituals, and local gods. Temples to Isis stood beside altars to Jupiter. Statues of Celtic river spirits appeared near shrines for Mithras. Roman religion became a mosaic reflecting the diversity of its subjects.

Foreign gods did not weaken Roman identity. They strengthened it by making Rome the crossroads of ancient spirituality. The empire’s religious inclusivity was a major reason it remained stable for centuries, offering every culture a place within its sacred landscape.