Deucalion and Pyrrha tell the Roman version of a story that echoes through many cultures — the flood that cleanses the earth and the rebirth that follows.

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Jupiter decides to purge a world corrupted by violence and deceit. Only one couple, Deucalion and Pyrrha, survive through faith and virtue. Their survival and the strange rebirth that follows symbolize moral renewal: the world destroyed by sin remade through reverence, endurance, and reason guided by divine favor.

Corruption of the Early Race

The myth begins in the Iron Age of humankind. Justice has fled, loyalty decayed, and impiety reigns. Mortals mock the gods, break oaths, and spill kindred blood. The last spark of righteousness is extinguished by Lycaon, a tyrant who tries to deceive Jupiter by serving him human flesh at a feast.

Outraged, the king of gods destroys Lycaon’s palace and transforms him into a wolf, revealing that savagery already lived within men before it appeared in beasts. Seeing that corruption has spread beyond redemption, Jupiter resolves to cleanse the world by flood.

The Flood

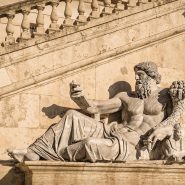

Jupiter gathers the clouds and commands the South Wind to pour forth endless rain. Neptune, striking the earth with his trident, releases rivers from their beds. Valleys vanish, mountains become islands, and all living creatures perish in the rising waters. Temples collapse, trees float uprooted, and even birds find no rest but on the shoulders of the drowning. The sea covers the face of the world, leaving only the pure and the fortunate alive.

Deucalion, son of Prometheus, and his wife Pyrrha, daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora, are spared for their piety and prudence. Guided by their virtue, they find safety in a small wooden boat that rides above the ruin.

Survival and Prayer

For nine days and nights, the waves roam over the earth until at last the vessel grounds upon Mount Parnassus. When the clouds part and the sea recedes, Deucalion and Pyrrha emerge into a silent world.

The land is barren and cold, and the air carries the weight of mourning. They give thanks to the gods and make an offering to Themis, goddess of justice and divine order. Their prayer is not for comfort, but for counsel. “How,” they ask, “can the race of man be restored, when all has perished?”

The Oracle’s Riddle

Themis answers through a cryptic oracle: “Cover your heads and throw the bones of your great mother behind you.” Confused and fearful of sacrilege, Pyrrha hesitates.

To cast aside their mother’s bones seems an impious act. But Deucalion, remembering his father Prometheus’s wisdom, interprets the riddle. The “great mother” is Earth herself, and her “bones” are the stones that form her body.

With reverence, they veil their faces and throw stones behind them as they walk. The stones cast by Deucalion grow into men; those cast by Pyrrha into women. Thus, humanity is reborn from the earth that once buried it.

The New World

As life returns, rivers find their courses, forests reappear, and animals rise from the damp soil. The sun warms the fields, and creation begins anew, gentler than before.

Deucalion and Pyrrha, though now surrounded by others, remain the moral parents of the new race. Their example teaches that survival is not enough — virtue must guide renewal.

Where Lycaon had mocked the gods, they honored them. Where the world had been loud with cruelty, they rebuilt it through quiet labor and prayer.

Symbolism and Interpretation

The flood signifies the moral cleansing that follows the collapse of justice. In Roman philosophy, it reflected a cosmic rhythm: corruption gives way to renewal, destruction to rebirth. Deucalion and Pyrrha represent reason and conscience working together — intellect interpreting divine signs, and reverence obeying them. Their act of throwing stones reveals that even rebirth demands effort and understanding.

The new humanity born from stone suggests endurance as the foundation of virtue. The myth, while echoing Greek and Near Eastern precedents, carries Rome’s own lesson: that moral order must be continually rebuilt by those who remember the gods.

Cultural Legacy

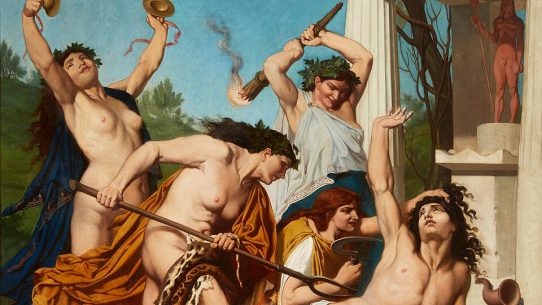

Ovid’s account shaped Roman thought about catastrophe and regeneration. Philosophers read it as an allegory for the cycles of empire — the fall of arrogance and the restoration of law. Artists painted the deluge not merely as destruction but as purification.

Later Christian writers would see in Deucalion and Pyrrha a foreshadowing of the Ark, the just saved through water. Yet the Roman message remains distinct: renewal is achieved not by divine favor alone, but by the human choice to act rightly when the world begins again.

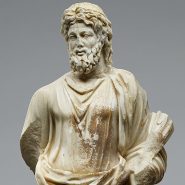

Gods involved: Jupiter, Neptune, Themis.

Based on classical sources in the public domain, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses and related translations available via Project Gutenberg and Wikisource.