Orpheus and Eurydice is one of Rome’s most haunting love stories — a tale that unites music, loss, and faith against the silence of death.

Through Orpheus, the singer who could charm stones and trees, the myth explores art’s power to bridge worlds. Yet even song cannot escape the law of mortality. In his descent to the underworld, Orpheus learns that love can move the gods, but not overturn the conditions of life.

The story stands as a meditation on hope, art, and the limits of human longing.

Characters and Setting

Orpheus, son of the muse Calliope and the Thracian king Oeagrus, was taught to play the lyre by Apollo himself. His music could calm beasts, bend rivers, and draw the forest after him.

Eurydice, his beloved, was a nymph whose grace matched his song. Their union seemed blessed, a harmony of art and nature. But in the meadows of Thrace, where they walked on their wedding day, tragedy came as swiftly as inspiration departs.

The myth unfolds in both worlds — the sunlit fields of the living and the shadowed halls of the dead — bound together by the echo of a single melody.

The Loss

Not long after their marriage, Eurydice wandered through the grass with her companions, gathering flowers. A serpent, hidden among the reeds, struck her heel. The venom spread like dusk across her veins. She fell, and the chorus of the forest went silent.

When Orpheus learned of her death, his voice became lament. His music, once filled with joy, turned into a plea. The mountains wept, and even the gods heard. But grief would not stop at lamentation. Orpheus resolved to descend into the underworld to bring her back.

The Descent

With his lyre across his shoulder, Orpheus crossed the thresholds that divide life from death. He entered the caverns of the underworld, where shadows drifted and the waters of Lethe murmured forgetfulness. At his song, the torments paused. Ixion’s wheel stood still, Tantalus forgot his thirst, and the Furies set down their whips. Cerberus, the three-headed guardian, lay down his growl and rested. Even the iron heart of Pluto and the sorrowing gaze of Proserpina softened. The music carried the memory of light into a realm without dawn. It was not rebellion but petition — beauty kneeling before law.

The Bargain

Pluto granted what no mortal had achieved: Eurydice could return to life. Yet the gift came with a single condition — Orpheus must walk ahead and not look back until both had reached the upper world. It was a test not of courage but of faith.

Between them stretched the long path of darkness, where doubt grows louder than sound. Orpheus took her hand and led her upward, his lyre silent now. The silence itself was trust, for to sing would have meant to turn.

But when the light of the surface began to shimmer before them, fear overcame obedience. He turned — and in that heartbeat, Eurydice vanished like breath on glass.

The Second Loss

Her final words were faint as mist: a farewell without reproach. The rocks heard them, and even they seemed to grieve. Orpheus reached out, but only the echo remained. He descended again to the gates, but Charon refused passage a second time.

Grief became his companion. He wandered the forests, singing to the memory of the one he had lost twice. His song tamed the wild and sanctified sorrow itself.

In his lament, Rome would later hear a reflection of its own struggle — to reconcile love and duty, beauty and loss.

Death and Transformation

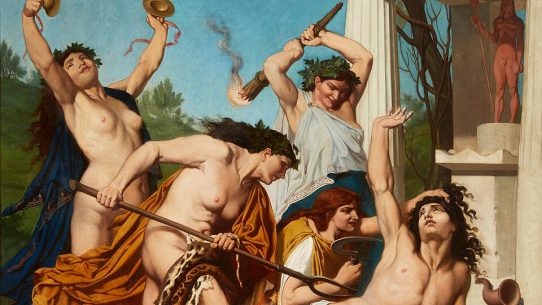

In some tellings, Orpheus renounces the love of women and dedicates himself to Apollo’s art. In others, he is torn apart by the Maenads, who cannot bear the purity of his grief.

His lyre, flung into the river, continues to play as it floats to the sea. The Muses gather his limbs and bury them at the foot of Mount Olympus, where birds still sing sweeter than elsewhere.

In this way, the artist becomes immortal not through survival, but through memory — the melody that refuses to die.

Symbolism and Interpretation

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is the Roman meditation on art’s boundary with truth. The descent mirrors the artist’s journey into the soul’s hidden chambers, where love seeks what death has taken. The backward glance is not mere weakness but the moment when passion eclipses obedience. It asks whether art’s yearning for perfection can coexist with the world’s unyielding order.

Orpheus fails as a savior but triumphs as a witness. His loss becomes Rome’s reminder that beauty cannot conquer death, yet it can transfigure grief into meaning.

Cultural Legacy

Through Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Virgil’s Georgics, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice entered the Roman canon as both love elegy and moral allegory. Poets and philosophers interpreted it as a drama of faith, while musicians saw in it the sacred origin of their art. Later generations — from medieval theologians to Renaissance painters — found in Orpheus the emblem of harmony and sacrifice.

In Roman thought, he stands beside Aeneas as the soul who dares to enter death for love of the living. The lesson is bittersweet: faith falters, but beauty remembers.

Gods involved: Pluto, Proserpina, Apollo

Based on classical sources in the public domain, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Virgil’s Georgics, with translations available via Project Gutenberg and Wikisource.