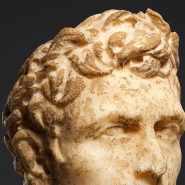

Hercules embodies the Roman ideal of strength in service to duty. His life, scarred by trials and hardened by atonement, ends not in oblivion but in transformation.

The myth of his apotheosis — the ascent from mortal toil to divine honor — teaches that endurance joined to virtue becomes worthy of the gods. Through labors, loss, and final conflagration, the hero is refined like iron in a furnace until he shines with immortal light.

Birth and Burden

Born of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmene, Hercules is the sign of power bound to purpose. From infancy, Juno’s jealousy pursues him. He survives serpents in the cradle and grows into a man whose strength continually threatens to become mere violence.

Fate, however, sets a path that transforms strength into service. After a madness — a calamity that leaves him guilty and grieving — he seeks purification. The oracle prescribes years of labor under Eurystheus, king of Tiryns. He bows his neck to the yoke of justice.

Labors as Education

The labors are an education in measure and craft.

The Nemean Lion falls to his hands when brute force meets cunning. The Lernaean Hydra demands strategy and fire. The Erymanthian Boar and the Ceryneian Hind teach patience. The stables of Augeas require ingenuity as much as muscle. The girdle of Hippolyta, the mares of Diomedes, the cattle of Geryon, the apples of the Hesperides — each task draws him across the world’s edges where human limits meet divine tests.

The capture of Cerberus, last and darkest, proves mastery of fear itself. The labors tame more than monsters. They tame the hero’s heart.

Between Tasks: Deeds and Tragedies

Between the formal labors, Hercules performs works of defense and rescue, yet his life remains perilous. He frees Prometheus, lifts cities from siege, and wrestles with personified rivers. He also suffers reversals that show the cost of power without respite. The centaur Nessus dies by his arrow and leaves behind treacherous counsel that will one day prove fatal. Glory accumulates while vulnerability gathers in secret.

Deianira’s Gift

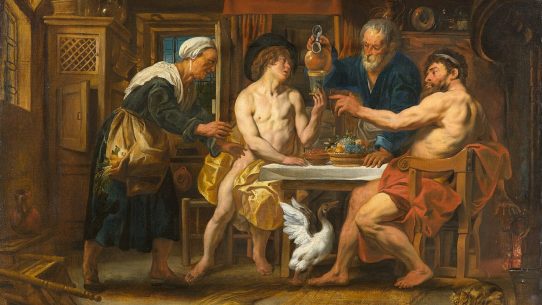

After the labors, Hercules marries Deianira. In time, jealousy and fear seep into the marriage like slow poison. Nessus, dying, had told Deianira that his blood would preserve faith if ever Hercules’ love should wander.

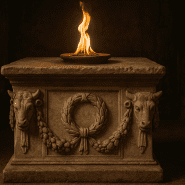

When rumor reaches her that Hercules desires Iole, Deianira sends him a tunic steeped in the centaur’s blood. The false charm is, in truth, a corrosive venom. As Hercules prepares a sacrifice on Mount Oeta, the tunic clings and burns. No water soothes it. No strength can tear it free.

The hero roars not at fate but at the cruelty of a poisoned trust.

The Pyre on Oeta

Hercules will not be consumed by slow torture. He commands a pyre to be built. Friends falter before the task until the shepherd Philoctetes steps forward.

Hercules lies upon the wood with the steadiness of one who has faced beasts and kings and now faces pain with equal courage. The fire ascends. Mortality burns away like a husk. The air brightens around the flames as if the heavens themselves are drawing a breath to receive a purified life.

Ascent and Transformation

Jupiter, who sees the balance of justice and mercy, declares before the gods that Hercules has earned a place among them. The thunder speaks; the flames become a chariot. The body is shed; the virtue remains.

Hercules ascends to Olympus where he is reconciled with Juno and weds Hebe, goddess of youth. His sufferings, once punishment, are transfigured into honor. The man who learned to govern force becomes strength crowned with peace.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Hercules’ apotheosis is not an escape from consequence. It is the answer to a life wrestled into meaning. The labors signify the disciplining of appetite and anger; the tunic, the tragic risk of human love; the pyre, the final act of courage that accepts the limit of flesh.

In Roman moral imagination, Hercules proves that virtue is forged — not granted — and that greatness must be purified before it can be trusted with authority. His ascent offers Rome an image of honor earned through work, restraint, and sacrificial fidelity.

Cultural Legacy

From temples to triumphal arches, Rome invoked Hercules as a patron of labor and guardianship. Artists carved his lion skin and club as shorthand for tested strength. Philosophers held him up as a model for the ruler’s burdens: a reminder that power must carry the world, not crush it. The myth’s final consolation — a bride of youth, a seat among the immortals — is Rome’s way of saying that the city believes in reward beyond hardship, and that the highest reward is to belong to a moral order that outlasts pain.

Gods involved: Jupiter, Juno, Hebe

Based on classical sources in the public domain, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses and other translations available via Project Gutenberg and Wikisource.