Among the countless festivals that filled the Roman calendar, none matched the exuberance of Saturnalia. Held in honor of Saturn, the ancient god of agriculture and time, this winter festival embodied the spirit of joy, freedom, and social upheaval.

For a brief period each December, the rigid hierarchies of Roman society dissolved, and chaos became celebration. Masters served slaves, gambling was permitted, and laughter echoed through the streets of Rome — all in the name of Saturn’s golden age.

Origins of the Festival

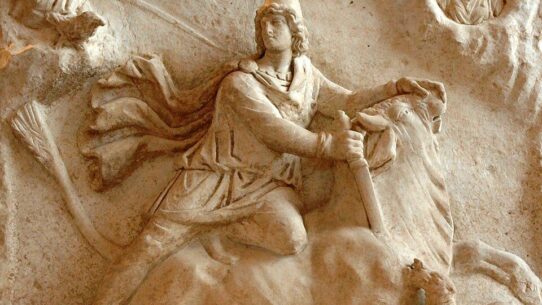

The Saturnalia was one of the oldest Roman festivals, its origins stretching back to the early Republic, possibly even earlier. It honored Saturn, a god associated with sowing and harvest, whose reign, according to myth, marked an age of peace and equality before the rise of Jupiter and the Olympian gods.

The festival began on December 17, later extended to a week-long celebration. Its timing coincided with the winter sowing season, symbolizing hope for renewal and abundance. The Roman historian Livy recorded that the earliest celebrations took place at the Temple of Saturn in the Forum, where priests unveiled the god’s statue, traditionally bound in woolen straps throughout the year. The untying of these bonds marked the release of Saturn’s spirit — a moment symbolizing liberation and joy.

Rituals and Celebrations

The festival opened with solemn sacrifices at Saturn’s temple, followed by a public feast attended by citizens of all classes. But soon the formality gave way to revelry. Homes were decorated with greenery, candles, and garlands; friends exchanged gifts, especially wax figurines (sigillaria) and small candles (cerei), symbolizing light’s triumph over darkness during the year’s longest nights.

The most striking feature of Saturnalia was social reversal. During the festival, social norms were suspended:

- Slaves dined alongside their masters and were even served by them.

- Formal togas were replaced by colorful caps called pilei, symbols of freedom.

- Gambling, normally forbidden, was openly practiced.

- Public order relaxed as laughter, feasting, and song filled the air.

These customs reflected the belief that Saturn’s age — the mythical Golden Age — was a time when all people were equal and lived in harmony without toil or tyranny.

The Lord of Misrule

A unique Saturnalian tradition was the election of a “King of Misrule” (Saturnalicius princeps), a mock ruler chosen to preside over the festivities.

This figure issued humorous orders and commands, often ridiculous or satirical, which everyone was expected to obey. The temporary king embodied the spirit of reversal and excess, a living reminder that even Rome’s disciplined society needed moments of release.

Symbolism and Meaning

At its core, Saturnalia represented renewal through inversion. By turning order upside down, Romans believed they refreshed the cosmic balance and appeased Saturn’s ancient, unpredictable power. The laughter and liberty of the festival were not rebellion but ritual — a sanctioned chaos that reaffirmed social stability once normal life resumed.

It also carried agricultural symbolism: the god Saturn presided over sowing, and the revelry of Saturnalia reflected the cycle of death and rebirth inherent in the seasons. Just as the earth rested in winter before the spring planting, Roman society rested from its usual discipline before returning renewed.

Influence on Later Traditions

Saturnalia’s influence extended far beyond pagan Rome. As Christianity spread, elements of the festival blended with new winter observances. Gift-giving, feasting, and the spirit of joy would resurface in Christmas celebrations, while the misrule and masquerades of Saturnalia echoed in Carnival and Mardi Gras traditions centuries later.

Even the image of social equality — the idea that, for a time, all distinctions vanish — persisted as a powerful cultural memory. The Saturnalian dream of freedom, though temporary, spoke to a deep Roman yearning for the lost Golden Age and the hope of renewal amid life’s hierarchies.

Conclusion

The Saturnalia was more than a festival; it was a joyful suspension of the ordinary world. In its laughter and chaos, Romans found renewal and connection to their mythic past. The god Saturn, once unbound, reminded them that order and freedom, discipline and joy, were both essential to the harmony of life.

For a few precious days each winter, Rome danced backward through time — to an age when the fields were fertile, the people were free, and all were equal under the sun.