The fall of the Roman gods was not a sudden event — it was a slow, complex transformation that unfolded over centuries. The same empire that once built marble temples to Jupiter and Venus eventually raised basilicas to Christ and the saints.

Yet Roman mythology did not vanish when Christianity triumphed. It adapted, concealed, and evolved, leaving traces that still color the symbols, language, and imagination of the Western world.

To explore the decline of Rome’s ancient religion is to witness one of the most fascinating cultural metamorphoses in history. It is a story of coexistence, rivalry, and eventual fusion between two worlds: one of myth and one of faith.

The Last Age of the Old Gods

By the second century CE, Roman religion had reached its peak of ritual sophistication. Every festival, harvest, and battle was governed by divine law. The gods of the state — Jupiter, Mars, Minerva — embodied the power of empire. Yet as Rome expanded, it absorbed foreign beliefs with remarkable openness. Egyptian, Persian, and Syrian cults found homes within the city’s walls. Isis, Mithras, and Cybele all became rivals to Jupiter in the hearts of Romans.

This cosmopolitan faith reflected the empire’s diversity, but it also revealed a restlessness of spirit. The old gods were distant and formal, bound to ceremony rather than compassion. People longed for a religion that promised personal salvation rather than collective prosperity. Into this spiritual vacuum came Christianity.

The Clash of Worlds

Christianity began as a small Jewish sect, but its message of redemption and equality appealed to Rome’s oppressed and enslaved populations. Unlike the state cults, it asked for faith rather than ritual precision. Its God was not one among many but the creator of all. This theological exclusivity set it on a collision course with the Roman way of worship.

In the early centuries, the empire viewed Christians as subversive. Their refusal to honor the emperor’s divine status was seen as rebellion. Yet persecution could not suppress the new faith. As philosophers, soldiers, and aristocrats converted, Christianity spread through the empire’s veins, challenging the ancient gods’ dominion.

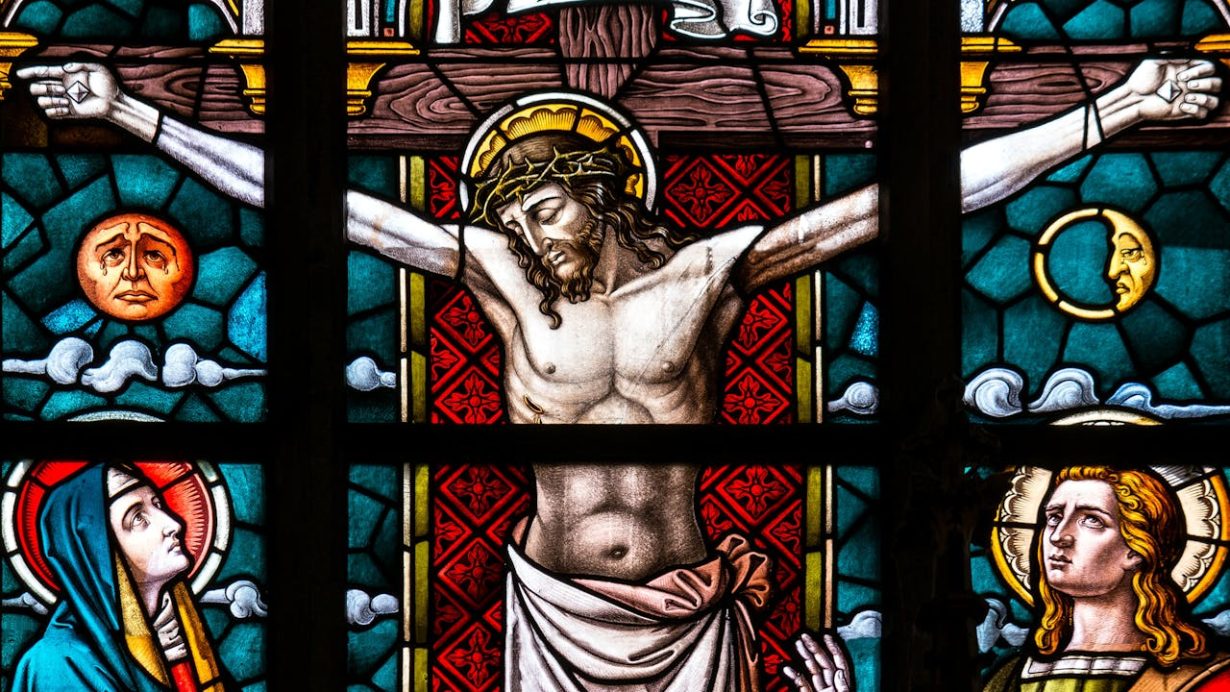

When Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity in the early fourth century, the balance shifted permanently. Pagan temples were closed or repurposed. Sacrifices ceased. The rituals that once bound Rome’s identity faded into memory. But mythology, resilient as ever, refused to die.

Survival Through Transformation

Many aspects of Roman religion quietly merged into the Christian world. Festivals such as Saturnalia influenced Christmas traditions. The imagery of the Virgin Mary drew upon ancient depictions of goddesses like Isis and Venus. The Roman calendar, temple architecture, and even the Latin language remained intact. Saints replaced minor deities as guardians of trades, families, and regions.

The Church’s early theologians often reinterpreted pagan stories rather than rejecting them outright. Philosophers like Augustine acknowledged the beauty and moral insight found in classical myths, using them as allegories for Christian truth. The gods who once ruled Olympus were transformed into poetic symbols — echoes of human longing for the divine.

Art and the Afterlife of Myth

Even as faith changed, art preserved Rome’s mythology. The Renaissance, driven by curiosity and admiration for the classical world, restored Jupiter, Venus, and Mars to the center of artistic imagination. Painters like Raphael and sculptors like Michelangelo saw no contradiction in celebrating pagan beauty alongside Christian devotion. For them, myth was the language of nature and creativity, not heresy.

In literature, Roman mythology continued to guide moral and philosophical inquiry. Dante, Milton, and later poets drew from the imagery of Olympus to describe Christian visions of heaven and hell. The gods had fallen, but their symbols remained potent. Through art and allegory, they achieved a new immortality — one born not of worship, but of memory.

Echoes in the Modern World

Today, traces of Roman mythology still shape our cultural landscape. The names of planets, months, and celestial bodies recall ancient gods. Political power borrows the visual language of Roman authority — columns, eagles, laurel wreaths. Even our stories of heroes and destiny echo the moral codes once taught by Jupiter’s council.

In a sense, Rome’s mythology never truly fell. It simply transformed into mythic language — the shared vocabulary of Western imagination. Its gods may no longer receive offerings, but they continue to guide art, literature, and identity through symbolism as powerful as any prayer.

Conclusion

The transformation of Roman mythology under Christianity reveals a deep truth about human culture: no belief system ever disappears completely. It adapts, evolves, and reemerges in new forms. The gods of Rome lost their temples but not their relevance. In art, language, and ritual, their presence endures — a quiet reminder that even in faith’s revolutions, myth remains eternal.