Roman mythology is often misunderstood as a fixed pantheon copied from Greece and lightly adapted for Roman tastes. In reality, Roman religion was one of the most flexible and absorptive mythological systems in the ancient world.

As Rome expanded beyond Italy and came into sustained contact with the civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean, Anatolia, Persia, and Egypt, it did not merely conquer lands. It encountered ancient religious traditions that profoundly reshaped how Romans understood gods, fate, salvation, and cosmic order.

These eastern influences did not dilute Roman religion. They strengthened it. By selectively absorbing foreign myths and deities, Rome transformed its religious system into a vast, interconnected network capable of governing an empire of extraordinary diversity.

This article serves as an overview of how mythic borrowings from the East entered Roman religion, why they were accepted, and how they permanently altered Roman spiritual life.

Roman Religion Before Eastern Influence

Early Roman religion was pragmatic, ritual-focused, and deeply civic. The gods were protectors of contracts, boundaries, agriculture, warfare, and the household. Religious success depended not on belief or theology but on correct ritual performance and reciprocal obligation.

This system worked well for a city-state and even for an Italian power. However, as Rome expanded into the eastern Mediterranean, it encountered cultures with religious traditions that emphasized ancient cosmologies, sacred kingship, personal salvation, and mystical union with the divine. These ideas exposed the limitations of Rome’s older religious framework and created opportunities for transformation.

Why Rome Was Open to Foreign Gods

Rome’s willingness to adopt eastern gods was not accidental. It was built into the logic of Roman religion itself.

Roman authorities believed that divine power was not exclusive. If a god demonstrated efficacy, protection, or prophetic insight, that god deserved recognition. Foreign origin was not a disqualification. In many cases, it was a sign of proven antiquity and authority.

Equally important was Rome’s political instinct. Incorporating local gods helped stabilize conquered territories, legitimize Roman rule, and integrate diverse populations into a shared religious framework. Religion became a tool of governance as much as devotion.

Pathways of Eastern Influence

Eastern myths entered Rome through long, overlapping processes rather than sudden adoption.

Trade networks connected Rome to Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia, bringing merchants and sailors who practiced foreign rites in port districts and urban neighborhoods. Military campaigns exposed Roman soldiers to eastern cults that promised protection, loyalty, and cosmic meaning amid danger and displacement. In moments of crisis, Roman leaders actively sought divine guidance from beyond Italy, importing cults believed to possess exceptional power.

Over time, these practices moved from private worship into public life, often after periods of suspicion, restriction, and eventual acceptance.

The Cult of Mithras and the Eastern Cosmos

One of the most influential eastern-inspired religions in Rome was the Cult of Mithras. While drawing inspiration from Indo-Iranian traditions, Roman Mithraism developed into a distinct system that reflected Roman values of hierarchy, discipline, and loyalty.

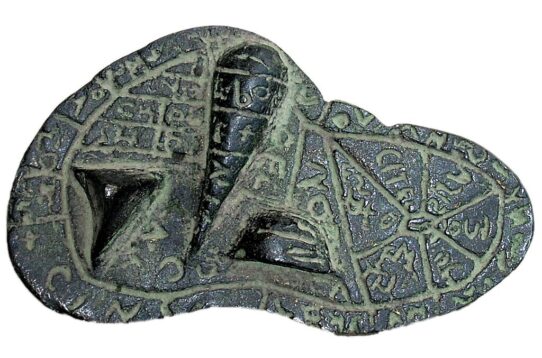

Central to Mithraic imagery was the tauroctony, the mythic slaying of a bull, surrounded by zodiacal symbols and cosmic imagery. This scene conveyed a vision of the universe governed by order, sacrifice, and renewal. Initiates progressed through ranks that mirrored military structure, reinforcing bonds of secrecy and allegiance.

Mithraism appealed especially to soldiers and imperial administrators, revealing Rome’s growing fascination with eastern cosmology and personal initiation into sacred knowledge.

Isis and the Emotional Turn in Roman Religion

The Egyptian goddess Isis represented a different but equally transformative influence. Her cult offered emotional intimacy, compassion, and the promise of life beyond death, elements largely absent from traditional Roman state religion.

Isis was worshipped as a universal mother, healer, and savior. Her myths emphasized suffering, devotion, and rebirth, resonating deeply with individuals seeking personal connection rather than civic obligation alone.

Although Roman authorities periodically suppressed her cult, fearing its foreign rituals and strong emotional appeal, Isis endured. Her temples became fixtures in Rome itself, her imagery fully integrated into Roman artistic and religious expression.

Cybele, Attis, and Controlled Ecstasy

The Anatolian mother goddess Cybele, worshipped in Rome as Magna Mater, was officially imported during a time of national crisis. According to prophecy, her presence would secure Rome’s survival against existential threats.

Cybele’s worship introduced ecstatic rituals, sacred music, and the myth of Attis, a story of death, madness, and rebirth. These themes were powerful and potentially destabilizing, prompting Rome to regulate her cult carefully.

This balance illustrates Rome’s broader strategy with eastern religions: absorb their power while containing their excesses. The state controlled priesthood, ritual expression, and public display, ensuring that emotional intensity served, rather than challenged, Roman order.

Sol Invictus and Imperial Theology

Eastern solar worship played a crucial role in reshaping Roman imperial ideology through the cult of Sol Invictus. Drawing from Syrian and Persian solar traditions, Sol Invictus symbolized cosmic stability, renewal, and divine kingship.

As the empire grew more diverse and politically fragile, solar imagery offered a universal language of power. The sun ruled all lands equally, just as the emperor claimed authority over all peoples. Sol Invictus became a bridge between eastern cosmology and Roman state religion, reinforcing imperial legitimacy during periods of crisis.

Syncretism as Translation, Not Replacement

Roman mythic borrowing did not erase older gods or traditions. Instead, it translated them. Eastern deities were reinterpreted through Roman names, symbols, and institutions, allowing them to coexist with traditional Roman gods.

This process of syncretism created hybrid forms that felt both ancient and familiar. Foreign myths retained their perceived power while becoming intelligible within Roman cultural norms. The result was a layered religious system capable of accommodating profound diversity without fragmentation.

Preparing the Ground for Later Transformations

By the late empire, eastern religious ideas had reshaped Roman spirituality at every level. Household worship included foreign gods. Military religion emphasized salvation and cosmic struggle. Imperial theology drew heavily on eastern symbolism of light, renewal, and divine authority.

This environment prepared Rome for even greater religious change. The spread of Christianity occurred within a culture already accustomed to eastern concepts of redemption, sacred history, and universal divinity.

Rome as a Mythological Crossroads

Mythic borrowings from the East were not signs of Roman weakness or indecision. They were expressions of confidence. Rome believed its identity was strong enough to absorb the sacred traditions of others without losing itself.

Understanding these borrowings reveals Roman mythology as a living system shaped by encounter, adaptation, and empire. Rome did not simply inherit myths. It transformed them into tools of survival, unity, and meaning.