Introduction

In the heart of Roman religion stood the altar — a sacred platform that bridged the mortal and the divine. Whether in grand temples or humble homes, the altar was where Romans made offerings, expressed devotion, and sought favor from the gods. It represented the center of spiritual life, a focal point for both personal faith and public ritual, embodying the bond between humanity and the celestial order.

Origins and Purpose

The Roman altar, or ara, drew inspiration from earlier Italic and Etruscan practices. Altars predated temples, existing first as simple stone or earthen mounds upon which sacrifices were laid. As Roman religion evolved, these primitive structures became more elaborate, adorned with carvings, inscriptions, and symbols of divine power. Yet their core function remained the same: to serve as a vessel of communication between the human world and the gods.

Each altar was consecrated to a specific deity. Public altars honored gods like Jupiter, Mars, and Vesta, while private altars within homes paid tribute to household spirits such as the Lares and Penates. The altar’s universality reflected Rome’s devotion to divine order in every sphere of life — from the governance of the empire to the intimacy of the family hearth.

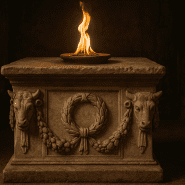

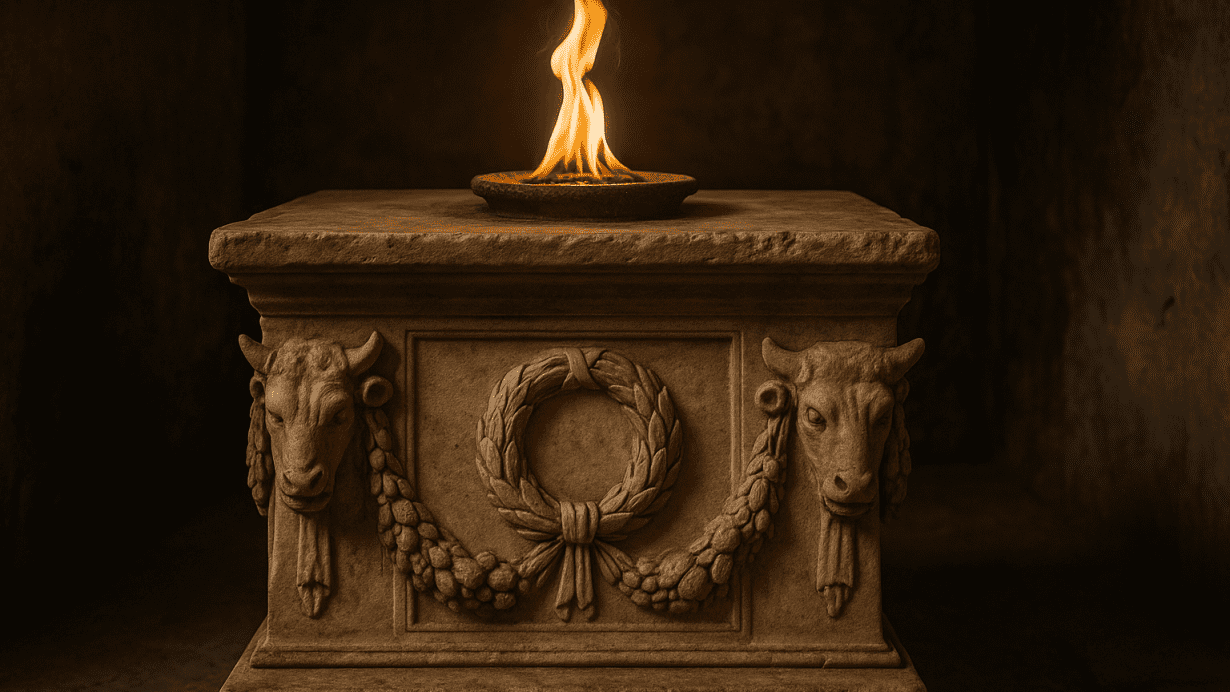

Symbolism and Structure

The altar symbolized both offering and transformation. Through the act of sacrifice, mortals transferred their prayers and gratitude to the gods, often by means of fire. Flames consumed animal sacrifices, incense, wine, or grain, carrying the offering upward as smoke — a visible sign of communion between heaven and earth.

Most Roman altars were rectangular or square, raised above the ground to elevate the offering closer to the divine. Carvings often depicted garlands, bulls’ heads, sacrificial tools, or mythological scenes related to the honored deity. Inscriptions such as V.S.L.M. (votum solvit libens merito, “willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow”) reminded observers of the reciprocity at the heart of Roman piety: gifts given, prayers answered.

The Role of the Altar in Ritual

Every Roman religious ceremony, whether domestic or state-sponsored, began and ended at an altar. Priests (pontifices, flamines, or augurs) purified the site, sprinkled salted meal (mola salsa) upon the victim, and prayed for divine acceptance before making the sacrifice. The flame’s reaction was often interpreted as a sign of the gods’ favor or displeasure.

In private life, families maintained small altars in their homes or courtyards. Morning and evening offerings of wine, honey, or incense to the household gods reinforced the Roman belief that divine forces were ever-present in daily affairs. Even emperors, despite their exalted status, were expected to perform sacrifices at the altars of the gods to affirm their piety and maintain cosmic harmony.

The Altar as a Political and Civic Symbol

Altars in Rome were not only religious centers but also political monuments. State altars such as the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) celebrated imperial virtues like peace, fertility, and order. Built in 9 BCE, the Ara Pacis became one of the most famous symbols of Rome’s golden age, merging religion, art, and propaganda. It depicted mythological and historical scenes that linked Augustus’s rule to divine will, reinforcing the emperor’s role as mediator between the gods and the people.

Similarly, military campaigns often included the erection of altars on conquered lands, signifying Rome’s divine mandate to rule. Through these sacred structures, religion and empire intertwined, sanctifying expansion and legitimizing authority.

Domestic Altars and Everyday Faith

For ordinary Romans, the household altar was the most intimate expression of faith. Small shrines known as lararia adorned with painted figures or terracotta statues provided a space for daily prayer. Families offered garlands, food, or small coins, invoking the protection of their ancestral spirits. These domestic rituals underscored a key feature of Roman religion: devotion was not confined to temples but infused into the rhythm of everyday life.

Festivals, births, and marriages were all accompanied by altar rites. Even travelers might carry portable altars to ensure divine favor on their journeys. In this way, the altar symbolized continuity — a portable axis of faith that followed Romans wherever they went.

Decline and Legacy

With the rise of Christianity, the meaning of the altar transformed but did not disappear. The Christian altar inherited much of its Roman symbolism: a table of offering, a site of divine communion, and a focal point of worship. The continuity reflects how deeply rooted the altar was in Roman consciousness. What began as a stone for sacrifices became a sanctified table for the Eucharist — a profound evolution of meaning across time.

Today, Roman altars survive as archaeological relics and museum treasures, their inscriptions and reliefs offering glimpses into a world where faith was public, material, and ever-present. They remind us that the altar, whether ancient or modern, remains humanity’s timeless gesture toward the divine.