Among the divine forces that shaped Roman life, none burned more brightly than Sol, the god of the Sun. He was the radiant charioteer who rode across the heavens each day, bringing light to gods and mortals alike.

Though often overshadowed by later solar cults such as that of Sol Invictus, the older Sol embodied one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring beliefs: that the Sun itself is a living power, eternal and divine.

The Ancient Origins of Sol

Sol’s worship stretches back to Rome’s earliest days, when farmers and shepherds depended on the rhythm of the Sun for survival. The Romans, like many ancient peoples, understood that the Sun governed all cycles — day and night, the growth of crops, and the change of seasons. In their eyes, Sol was not merely a celestial body but a god whose favor ensured abundance, clarity, and renewal.

The earliest depictions of Sol show him as a youthful figure crowned with rays of light, driving a golden chariot pulled by four fiery horses. His Greek counterpart was Helios, and the Romans readily borrowed many of his myths, yet they regarded Sol as uniquely Roman — a native guardian of their skies and the mark of divine order.

The name Sol simply means “Sun,” yet it carried a sacred gravity. Every sunrise was a renewal of his journey, a sign that the world was once again sustained by his warmth.

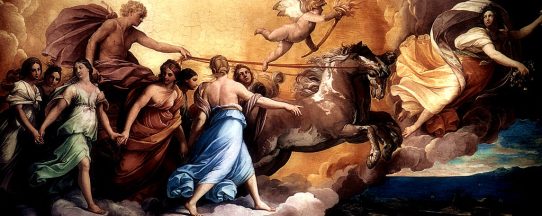

The Daily Journey Across the Sky

Each dawn, Sol would rise from his golden palace in the East, guiding his radiant horses across the firmament. His chariot’s wheels turned the heavens themselves, marking the passage of time. By dusk, he would descend into the Oceanus—the great river that encircled the world—and rest until the next day’s journey began.

To the Romans, this daily cycle was more than a physical event; it was a symbol of life’s eternal rhythm. Sol’s rising represented birth and hope, while his setting signified rest and renewal. The god’s ceaseless motion across the sky reminded mortals that even divine light must yield to darkness, only to rise again stronger than before.

Sol and Luna: The Celestial Pair

Sol was often depicted alongside his sister Luna, goddess of the Moon. Together they embodied the balance of opposites — light and shadow, day and night, activity and repose. Ancient Roman poets described their paths as harmonious yet separate: the two siblings rarely met, for when Sol began his descent, Luna’s silver chariot rose to take his place.

In art, Sol was portrayed with a crown of radiant beams, while Luna wore a crescent upon her brow. Their duality symbolized cosmic order, ensuring that time, seasons, and nature moved in perfect measure. This relationship inspired countless temples, altars, and festivals celebrating the divine dance between Sun and Moon.

The Festival of the Sun

Sol’s power was honored in several ancient rites, most notably the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti — the “Birthday of the Unconquered Sun” — celebrated on December 25. This date marked the winter solstice, when the days begin to lengthen again after the darkest point of the year. The Romans viewed this turning point as a rebirth of the Sun, a triumph of light over darkness.

Though the cult of Sol Invictus emerged later, under emperors such as Aurelian in the third century CE, it was deeply rooted in the older traditions of Sol. The emperor’s new religion emphasized Sol’s invincibility and universal power, portraying him as a divine protector of the empire. Soldiers carried his image, and the emperor himself was often depicted with a radiant halo—a symbol that would later influence Christian iconography.

Sol in Roman Religion and Art

Sol’s presence pervaded both daily ritual and public worship. The Romans invoked him at dawn, turning eastward in silent prayer. His image appeared on coins, mosaics, and triumphal arches. He was often depicted standing in a quadriga—the four-horse chariot—holding a whip or globe, symbolizing his dominion over the world.

One of the most famous representations of Sol stood atop the Colossus of Nero, a massive statue later adapted to represent the Sun god. In this form, Sol’s majestic figure overlooked Rome, a constant reminder that divine light watched over the city.

Temples to Sol existed throughout the Roman world, but the most significant was built by Emperor Aurelian around 274 CE. It stood on the eastern Campus Martius and became a center of state religion, merging traditional Roman piety with the new solar theology of the empire’s later centuries.

Sol and Apollo: A Divine Convergence

Over time, the identity of Sol began to merge with that of Apollo, the Greek god of light, music, and prophecy. By the late Republic and early Empire, poets and philosophers often used their names interchangeably. Apollo’s golden radiance, healing powers, and artistic grace blended naturally with the imagery of the Sun.

This fusion reflected the Romans’ tendency to harmonize their gods rather than replace them. Sol retained his cosmic sovereignty, while Apollo brought a more personal and intellectual dimension to the solar archetype. The result was a god who represented both the physical Sun and the illuminating force of knowledge.

Symbolism and Meaning

Sol’s symbolism ran deep in Roman thought. He was a god of clarity and truth, exposing all things to light. Nothing could hide beneath his gaze; he saw both the splendor and corruption of the mortal world. In this way, Sol became associated with justice and divine vision. To live “under the Sun” was to live within the sight of truth.

The Sun also represented constancy. In times of chaos or uncertainty, Sol’s daily return assured Romans that the universe remained orderly. Emperors invoked his favor to legitimize their reigns, and soldiers carried his image for courage and victory.

Yet Sol also carried a warning: his brilliance could blind as easily as it could illuminate. Excessive pride, or hubris, could draw down the Sun’s wrath, as seen in the myth of Phaethon, the reckless son who tried to steer his father’s chariot and perished in flames. The tale served as a moral reminder of mortal limits in the face of divine power.

The Enduring Legacy of the Sun God

Though official worship of Sol waned with the rise of Christianity, his legacy endured in art, language, and symbolism. The halo around saints and Christ echoes Sol’s radiant crown. The Latin word solis survives in modern languages — solar, solstice, solarium — each a quiet tribute to his enduring light.

Even the Christian celebration of Christmas, falling near the ancient festival of Sol Invictus, reflects how the Roman Sun god’s imagery blended into new faiths and traditions. In this way, Sol’s spirit continued to shine, transcending boundaries of religion and time.

The Light That Never Dies

To the Romans, Sol represented more than daylight — he embodied the divine certainty that life would always return after darkness. His chariot still rolls across the imagination of the world, eternal and unconquered. Whether as Helios, Apollo, or Sol Invictus, the god of the Sun remains one of humanity’s oldest and most universal symbols of hope.

Each sunrise, then as now, carries the same ancient promise: the assurance that light will always follow night, and that the flame of the divine never truly fades.