In the turbulent world of ancient Rome, where conquest and ambition defined greatness, the goddess Pax stood as a rare and radiant ideal. She was the embodiment of peace — not merely the absence of war, but the divine order that followed victory. Her presence promised stability, prosperity, and harmony among citizens and nations.

To the Romans, Pax was not weakness; she was the reward of strength, the calm that only empire could afford.

The Essence of Pax

Pax was the Roman goddess of peace, her Greek counterpart being Eirene. Yet the Romans made her something grander—an emblem of statehood and divine sanction. Pax personified not just the moral virtue of peace, but also the physical and political condition of it: fertile lands, safe trade routes, and a citizenry untroubled by fear.

To invoke Pax was to invoke the blessings of order and abundance. She was honored not as a passive ideal but as a living force — a deity whose favor sustained Rome’s Golden Age. Her cult gained prominence under Emperor Augustus, who used her image to symbolize the restoration of peace after decades of civil war.

The Augustan Ideal: Peace Through Power

When Augustus emerged victorious from the chaos of the Roman Republic’s civil conflicts, he sought not only to consolidate authority but also to legitimize it. Pax became the perfect symbol for this new era. Through her, Augustus declared that peace had returned — not through negotiation or surrender, but through the stability of imperial rule.

In 13 BCE, the Senate commissioned the Ara Pacis Augustae (“Altar of Augustan Peace”) to commemorate the emperor’s successful campaigns and the tranquility they brought. Completed in 9 BCE, the marble monument still stands as one of Rome’s most exquisite works of art. Its friezes depict scenes of abundance: children, animals, vines heavy with fruit, and the goddess Pax herself seated in serene majesty. The message was unmistakable — peace was the fruit of Roman power.

This intertwining of religion and politics transformed Pax from a domestic virtue into a divine expression of empire. She represented the Pax Romana, the “Roman Peace,” that stretched across the Mediterranean for more than two centuries.

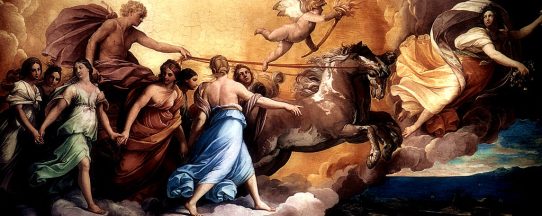

Symbols and Depictions

Artists and sculptors often portrayed Pax as a gentle, matronly figure. She was typically shown holding an olive branch, the ancient symbol of reconciliation, and a cornucopia, representing the plenty that peace brings. Sometimes she held a scepter, emphasizing her authority, or stood beside an altar adorned with doves or garlands.

On Roman coins, Pax’s image became widespread during the imperial period. Her likeness, accompanied by inscriptions such as PAX AUGUSTA or PAX ROMANA, served as both propaganda and prayer — reminding citizens that peace was secured under the emperor’s protection. Her figure appeared alongside other personifications like Felicitas (Happiness) and Concordia (Harmony), reinforcing the image of Rome as a benevolent and orderly realm.

Pax in Religion and Ritual

Though Pax did not have as ancient a cult as Jupiter or Mars, her worship carried immense civic importance. Temples and altars dedicated to her symbolized Rome’s aspirations toward unity and stability. The most famous of these was the Temple of Pax, constructed by Emperor Vespasian in 75 CE following his triumph over Judea. Located near the Roman Forum, it housed treasures seized from Jerusalem and served as both a sanctuary and a public space.

The goddess’s festivals reflected her dual nature: both divine and political. Citizens offered sacrifices for peace, but also celebrated military victories that ensured it. The Romans understood that peace had to be maintained through vigilance. Thus, Pax was not opposed to Mars, the god of war; rather, she was his necessary complement. As the poet Horace wrote, “After fierce battles, Peace returns in shining beauty.”

Pax and the Roman World

The influence of Pax extended beyond Rome’s borders. In provinces from Britannia to Syria, local deities were often identified with her, creating a shared divine language of peace and prosperity under Roman rule. Her image appeared on monuments, temples, and even provincial coins, signaling that the favor of Pax was the empire’s gift to all its subjects.

For Rome’s citizens, Pax was both spiritual and practical. She represented safe roads, trade routes free from bandits, ships that sailed without fear of pirates, and the steady flow of grain to feed the city. In art and literature, she was often depicted surrounded by abundance — a living metaphor for civilization itself.

Philosophical and Moral Dimensions

To the Romans, peace was not simply a divine blessing but a reflection of moral order. Pax embodied virtus (virtue) and iustitia (justice) made manifest in society. Philosophers such as Seneca and Cicero argued that true peace depended upon the harmony of the soul, just as civic peace relied on the virtue of leaders and citizens. Thus, Pax symbolized both the external calm of empire and the internal calm of self-mastery.

In this way, Pax bridged the divine and human realms. She was both goddess and ideal, reminding Romans that peace required discipline, wisdom, and respect for law. To neglect Pax was to invite chaos — the very anarchy that had nearly destroyed the Republic.

Decline and Transformation

As Christianity spread through the empire, the image of Pax began to merge with new ideas of divine peace. The early Christians saw Christ as the true bringer of peace, yet they often borrowed the familiar language of Pax to express it. The phrase Pax vobiscum — “Peace be with you” — echoed the goddess’s ancient blessing.

By the time of the late empire, Pax had faded from temples but not from memory. Her statues still stood, her symbols still appeared on coins, and her spirit survived in the Latin word pax, which remains the root of “peace” in many modern languages.

Legacy and Reflection

Pax’s legacy is profound and enduring. She represents one of humanity’s highest aspirations: a harmony born not from surrender, but from strength and justice. The Romans, for all their wars, understood that no empire could endure without peace as its foundation.

Today, the Ara Pacis still gleams beneath the Roman sky, a marble hymn to the goddess whose presence once defined an age. Pax reminds us that peace is not the absence of struggle — it is the outcome of wisdom, restraint, and compassion. In every era, her gentle image continues to whisper the same eternal truth: that the greatest victory is not won on the battlefield, but in the human heart.