Saturn, the ancient Roman god of time, wealth, and renewal, stood among the most complex and influential figures in Roman religion. He embodied both the golden past and the eternal cycles that govern nature and civilization.

To the Romans, Saturn was a paradoxical deity — stern yet generous, ancient yet ever-present. He ruled over agriculture, abundance, and the passage of time itself, ensuring that all things would wither only to rise again. His festival, the Saturnalia, was one of Rome’s most joyful celebrations, symbolizing freedom, equality, and the turning of seasons.

In Saturn’s mythology, the Romans found both reverence for the past and hope for renewal.

Name and Origin

The name “Saturn” is linked to the Latin root satus, meaning “sowing” or “seed,” reflecting his association with agriculture and creation. He was one of the oldest deities in the Italic pantheon, predating the influence of Greek religion.

Later, he was identified with the Greek Cronus, the father of Jupiter and ruler of the Titans. Yet unlike the grim figure of Cronus who devoured his children, Saturn was remembered by the Romans as a benevolent king who reigned over a mythical Golden Age — a time of peace, equality, and plenty.

In his worship, Romans honored not only the power of time but the moral ideals of balance and generosity.

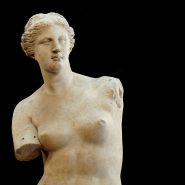

Attributes and Symbols

Saturn was often depicted as an aged man with a long beard, holding a sickle or scythe, symbols of both harvest and mortality. He was also shown with a covered head, representing mystery and the hidden forces of time. The sickle reflected his dominion over the cycles of life and death, while the seed and the grain signified fertility and abundance. The serpent, coiled upon itself, symbolized eternal return — time’s endless renewal. Gold, the metal of perfection, was sacred to him, as were agricultural tools and images of plenty.

Through these symbols, Saturn’s image bridged creation and decay, reminding Romans that every ending was a new beginning.

Family and Relationships

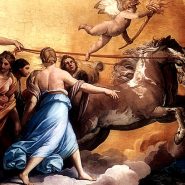

Saturn was the son of the primordial sky god Caelus (Uranus) and the earth goddess Terra (Gaia), and the father of several major deities, including Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto, Juno, and Ceres. Fearing that his children would overthrow him, Saturn swallowed each at birth, until Jupiter escaped this fate and ultimately fulfilled the prophecy.

After his defeat, Saturn was cast down from the heavens and came to Italy, where he brought agriculture and civilization to humankind. The Romans celebrated this arrival as the dawn of the Golden Age — an era of peace and prosperity under Saturn’s wise rule.

His consort was Ops, goddess of abundance and the harvest, whose partnership symbolized the union of labor and reward.

Myths and Stories

The myths of Saturn blended themes of time, creation, and redemption. His story began in conflict and ended in harmony — a cycle mirroring the seasons and the fate of humankind.

After being overthrown by Jupiter, Saturn found refuge in Latium, where the god Janus welcomed him. There, he taught the people to till the soil, cultivate crops, and live justly. This era became known as the Golden Age, when hunger and war were unknown, and all men were equal. In gratitude, the Romans built a temple to Saturn at the foot of the Capitoline Hill, its treasury symbolizing both the wealth of the state and the trust placed in divine order.

Another legend told that Saturn’s chains were loosed during his festival, the Saturnalia, representing the temporary suspension of order and the freedom of all people. Slaves and masters feasted together, gifts were exchanged, and joy replaced hierarchy. For the Romans, this was more than revelry — it was remembrance of a time when the world was whole and justice universal. Saturn’s myths reminded them that prosperity required humility before time’s eternal power.

Domains and Powers

Saturn ruled over agriculture, time, wealth, and renewal. As the god of sowing, he governed the planting of seeds and the hidden growth beneath the soil — both literal and symbolic. His influence extended to the passage of years, the cycles of decay and rebirth, and the preservation of abundance.

He was also patron of the Roman treasury (Aerarium), reflecting his association with material wealth and its responsible use. His power was vast but cyclical, ensuring that all things moved through phases of creation, decline, and return.

To worship Saturn was to acknowledge time’s dominion and the promise that even winter gives way to spring.

Philosophy and Moral Influence

Roman philosophers viewed Saturn as a moral teacher — a symbol of wisdom earned through age and reflection. He represented patience, moderation, and acceptance of change.

Stoics saw him as the divine principle of order within the passage of time, while poets like Virgil praised his reign as the model of virtuous governance.

Saturn’s Golden Age became a philosophical ideal, inspiring thinkers to seek justice and simplicity amid the corruption of later ages. His scythe reminded humanity that time spares none, yet through labor and virtue, renewal is always possible.

Saturn thus embodied the moral truth that endurance, not conquest, defines greatness.

Temples and Worship

The Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum was among the city’s oldest and most significant sanctuaries. Built around 497 BCE, it served as both a religious and civic center, housing the state treasury and official records. At its base stood a statue of Saturn bound with woolen bands, released only during the Saturnalia festival.

His worship emphasized gratitude and freedom, with offerings of grain, salt cakes, and wine. The Saturnalia, held each December, was Rome’s most joyous celebration: slaves were temporarily freed, gambling was permitted, and candles were exchanged to symbolize light returning after darkness. Through these rites, Romans renewed their faith in time’s endless cycle of decay and rebirth.

Legacy and Cultural Influence

Saturn’s legacy shaped both ancient and modern thought. His image endured as a symbol of time, fate, and maturity, inspiring the later figure of Father Time. The planet Saturn, slow-moving and majestic, was named in his honor, reflecting his association with endurance and wisdom. In art and literature, he represented both melancholy and reflection — the awareness that all beauty fades but returns in new form. The Saturnalia festival influenced later winter celebrations, including customs of gift-giving and feasting that survived into the modern era. Through Saturn, humanity found meaning in the passage of time: the understanding that change, though inevitable, brings renewal and hope.

Unique Traditions and Notes

During the Saturnalia, masters served their slaves, and all wore the pileus, a cap of freedom. Dice games, songs, and feasts filled the streets of Rome, and the usual decorum of society was joyfully overturned.

Offerings to Saturn were made without blood — only simple gifts of nature, reflecting his peaceful reign. His statue, veiled and bound for most of the year, was unwrapped during the festival, symbolizing liberation and abundance.

Even after the fall of pagan Rome, Saturn’s festival spirit endured in traditions of generosity and joy that celebrated renewal in the darkest days of winter.

Adapted from public-domain materials, including Project Gutenberg and Wikisource.