Few Roman festivals rivaled the Lupercalia in its mix of sacred ritual and earthy exuberance. Celebrated each year on February 15, this ancient rite honored Faunus — the Roman god of fertility, flocks, and the wild — as well as the legendary founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus.

What began as a rustic fertility ceremony evolved into one of the city’s most curious and enduring celebrations: a fusion of purification, vitality, and chaotic joy that revealed Rome’s deep connection to both nature and myth.

Origins and Mythic Associations

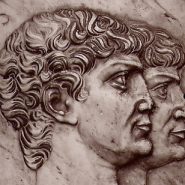

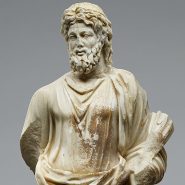

The name Lupercalia derives from the Lupercal, a cave on the Palatine Hill where, according to legend, the she-wolf (lupa) nursed the infant twins Romulus and Remus. This sacred site symbolized the primal bond between Rome and its divine protectors. The festival’s name and rituals also invoked Lupercus, a pastoral deity associated with Faunus and Pan, guardian of shepherds and fertility.

Ancient writers such as Livy and Plutarch linked the festival to early pastoral Rome, when shepherds sought divine favor for their flocks before the coming of spring. Others viewed it as a ritual of purification — a way to cleanse the city and ensure health and fruitfulness in the months ahead.

Rituals and Ceremonies

The Lupercalia began at the Lupercal cave, near the base of the Palatine Hill. There, priests known as the Luperci (“brothers of the wolf”) performed sacrifices, typically of goats and sometimes a dog, both animals symbolically linked to fertility and protection.

After the sacrifices, the Luperci smeared their foreheads with the blood of the animals, which was then wiped away with milk — a symbolic act of cleansing and renewal. Once purified, the priests feasted, drank wine, and prepared for the most famous part of the ceremony: the Lupercalian run.

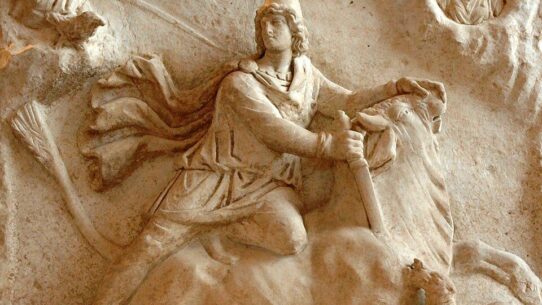

Wearing little more than strips of goatskin (februa), the Luperci ran through the streets of Rome, striking bystanders — particularly women — with thongs made from the sacrificial hides. Far from avoiding the blows, women welcomed them, believing they brought fertility, safe childbirth, and purification. This playful, even chaotic procession blurred the lines between the sacred and the sensual, embodying the raw vitality of life itself.

Symbolism of Purification and Fertility

At its core, the Lupercalia combined purification (februatio) and fertility magic, two forces essential to Roman conceptions of cosmic balance. February, in fact, takes its name from this very practice: the februa, or “instruments of purification.”

The festival’s mingling of animal sacrifice, ritual nudity, and communal laughter reflected the Roman belief that renewal required both symbolic cleansing and reconnection with nature’s primal energies. By shedding formality and embracing instinct, the people of Rome sought to renew not only their bodies but also the vitality of their city.

Civic and Social Dimensions

While rooted in rustic tradition, the Lupercalia eventually took on civic importance. By the late Republic, the festival involved prominent citizens and even political figures. Julius Caesar’s appearance at the Lupercalia of 44 BCE, when Mark Antony famously attempted to crown him king, marked one of history’s most dramatic intersections between ritual and politics.

This moment — immortalized by later writers — reflected how Rome’s ancient religious customs continued to shape its public life. Even as the Republic transformed into empire, the Lupercalia endured as a reminder of the city’s origins: a blend of piety, nature worship, and theatrical energy.

Decline and Legacy

The Lupercalia persisted well into the imperial period, though its meaning evolved. As Christianity spread, Church authorities sought to suppress the pagan festival. By the fifth century, Pope Gelasius I condemned it as an immoral relic of heathenism. In its place, the Church promoted new celebrations of purity and love — including, according to some historians, the feast of Saint Valentine, whose date fell near the Lupercalia’s traditional time.

Whether or not Valentine’s Day directly descended from Lupercalian custom, the connection between mid-February and themes of love, fertility, and renewal has endured for millennia.

Conclusion

The Lupercalia was one of ancient Rome’s most vivid expressions of the human impulse toward purification, passion, and rebirth. It bridged the civilized and the primal, the sacred and the sensual.

In honoring Faunus, Romulus, and the wild forces that sustained life, Romans celebrated not just fertility but the eternal rhythm of renewal. Though long vanished from the calendar, the festival’s spirit — joy, vitality, and the renewal of love — still flickers faintly in the modern heart of February.