Bona Dea occupies one of the most mysterious and sacred spaces in Roman religion. Her presence is felt in whispers, rituals, and carefully guarded secrets, rather than in grand epics or public monuments.

To the Romans, she was simply “The Good Goddess,” a title that deliberately concealed far more than it revealed. Her powers ranged from fertility to healing, purification, prophecy, and the protection of women at every stage of life. Yet everything about her worship was intentionally hidden from men. Bona Dea existed behind closed doors, in private rites surrounded by silence, candles, incense, and the company of women alone.

Her world was one of serenity and secrecy, a realm where women — who were often excluded from public rituals — held absolute authority. She represented the sacred interior life of Roman womanhood: its cycles, fears, strengths, and hopes. And although she left behind no surviving myths in the traditional sense, her influence shaped Roman society for centuries.

A Goddess Known Only to Women

Unlike goddesses such as Juno or Venus, Bona Dea did not have a public personality carved in marble or retold in heroic legends. Her worship belonged to the domestic and spiritual lives of Roman women, passed from mother to daughter, Vestal Virgin to noble matron. She had no male priests, no male attendants, and no male admirers allowed within her sanctuaries. Even her actual name — believed to be too sacred to speak — was concealed. “Bona Dea” was a respectful title used in place of her true, secret identity.

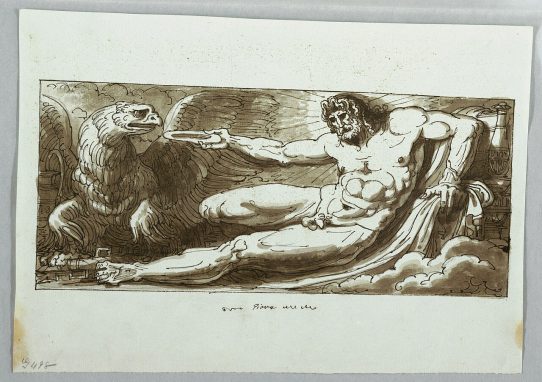

Her iconography was similarly restricted. Although she was often associated with serpents, herbs, healing tools, and symbols of fertility, her formal depictions remained intentionally vague, preventing outsiders from understanding the true nature of her rites. The absence of openly shared imagery only deepened her mystique.

This veil of secrecy did not diminish her importance. On the contrary, it elevated her. Romans believed that the more hidden and protected a deity was, the more potent her divine power became.

The Women-Only Sanctuary

Bona Dea’s primary temple stood on the Aventine Hill, a sacred refuge where women could pray, speak freely, and perform rituals without the presence or interference of men. Yet her most famous ceremonies took place not at her temple but within the home of the Pontifex Maximus each December. These rituals were among the most devoutly guarded traditions in Rome.

In preparation for the ceremony, the men of the household — including the highest priest of Rome himself — were required to vacate the property entirely. Male statues were covered, male animals removed, and the home was transformed into a sanctuary for women alone. Only the Vestal Virgins and invited Roman matrons could participate.

The rites were conducted at night, illuminated by lamplight and incense that filled the air with a sweet, heavy fragrance. Participants prepared offerings of wine—though within sacred language it was referred to only as “milk” — and a variety of healing herbs. The women gathered to honor the goddess’s power over fertility, purity, health, and transformation. Songs were sung, prayers whispered, and rituals performed that have never been fully recorded or described, because secrecy was itself part of the worship.

The exclusion of men during these ceremonies was not only symbolic but foundational. Bona Dea’s mysteries existed to give women spiritual autonomy, healing, and strength, without oversight from the male priestly class.

A Heavenly Protector of Women’s Health

Bona Dea’s devotion was strongest among women facing delicate or vulnerable moments: menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, infertility, or illness. Her sanctuary served as a spiritual refuge, a place where women asked for healing not just of the body but of the mind and heart.

Her connection to serpents — a symbol of regeneration and medicine — linked her to the ancient tradition of healing goddesses. The herbs used in her rituals echoed the remedies that Roman women relied upon to protect their families. Many believed she watched over the home, ensuring harmony and safety.

Midwives often invoked her for strength and clarity. Mothers prayed to her for protection of their children. Older women sought her aid in times of sickness or transition. In all cases, Bona Dea was not a distant cosmic power but a deeply intimate guardian.

The Scandal That Shook Rome

In 62 BCE, Bona Dea became the center of one of the most sensational scandals in Roman history. Publius Clodius Pulcher, a young and scandal-seeking aristocrat, disguised himself as a woman and infiltrated the December rites. His goal — whether romantic, political, or simply mischievous — is still debated, but the consequences were immense.

His presence violated the sanctity of Bona Dea’s mysteries and sparked public outrage. The idea that a man had intruded into a sacred space reserved exclusively for women was seen not only as sacrilege but as an assault on Roman religious identity.

Clodius was put on trial, and although he escaped conviction through bribery and political maneuvering, the episode highlighted how deeply Bona Dea’s worship was stitched into Roman culture. Even those who were not devotees recognized that her rites were a cornerstone of Roman moral and religious structure.

The Quiet Strength of a Hidden Goddess

What makes Bona Dea extraordinary is how she shaped Roman spirituality without ever stepping into the public eye. She did not require temples grander than Jupiter’s or stories more elaborate than those of Apollo. Her power lay in her invisibility, her secrecy, and her ability to create a private world where women’s experiences were revered.

Her festivals preserved a sense of feminine belonging, community, and autonomy that was rare in Roman society. For many women, worshiping Bona Dea was a reminder that divinity lived not just in battlefields, councils, or public triumphs but also in the quiet rhythms of their lives.

She represented the wisdom passed silently between generations, the healing arts practiced in kitchens and gardens, and the resilience embedded in the everyday journeys of Roman women.

A Legacy Rooted in Mystery

Today, Bona Dea remains one of the least understood yet most compelling figures in Roman mythology. The layers of secrecy around her worship have ensured that much of her story will forever remain hidden. But what survives speaks to a goddess who gave Roman women something rare and powerful: a space of their own.

She stands as a symbol of sacred privacy, feminine strength, and the enduring idea that some mysteries are meant not to be revealed, but cherished.